IDDRI and the HotorCool Institute have been working for several years on the social conditions of the ecological transition through the prism of the social contract. An initial historical study was conducted (IDDRI, 2024a), followed by an empirical exploration among citizens, with a specific focus on France and the United Kingdom (IDDRI, 2024b). One initial observation emerges: there is a strong attachment to historical social contracts, but these contracts are fragile, destabilizing our democracies and weakening our ability to drive the transition. We wanted to go further by proposing an empirical assessment at European level based on several dozen indicators (IDDRI, 2026). Which aspects of the contract are the most problematic or, on the contrary, still functional? What disparities exist within Europe? And how has the situation evolved over the last 10 years?

Building a social contract dashboard as a political roadmap

Understanding society as a “social contract” is a fruitful approach, in that it reveals the major compromises that structure our lives. In Europe, these compromises are organized into four ‘pacts’–Work, Democracy, Consumption and Security–which are equally important spheres of life, and whose commitments must be upheld in order for society to function, for collective rules to be respected, and for citizens to continue to believe in social progress.

Figure 1. The countries in the dashboard

To translate this approach into data, we selected 49 indicators from multiple data sources covering 31 European countries with sufficient historical perspective. We selected indicators consistent with European citizens’ majority view of a ‘fulfilled’ social contract based on our historical and empirical work: good democratic representation, economic redistribution, ability to plan for the future, etc. The originality of our approach also stems from the fact that we have combined objective and subjective indicators–based on the idea that perceptions and emotions (recognition, loss of control over the future, etc.) also reveal the state of the social contract.

Below are a few examples that illustrate the type of indicators used and this objective/subjective complementarity.

- Democracy Pact: proportion of female MPs (objective); feeling of being represented by elected officials (subjective);

- Security Pact: homicide rate (o); perceived insecurity (s);

- Work Pact: unemployment rate (o); feeling of receiving sufficient recognition for one's work (s);

- Consumption Pact: income growth (o); feeling of being able to make ends meet (s).

This unprecedented work required simplifications and choices: although necessarily imperfect in representing the richness of our social contract, it nevertheless provides valuable insight (IDDRI, 2026).

Which aspects of the contract are the most problematic or, conversely, still functional?

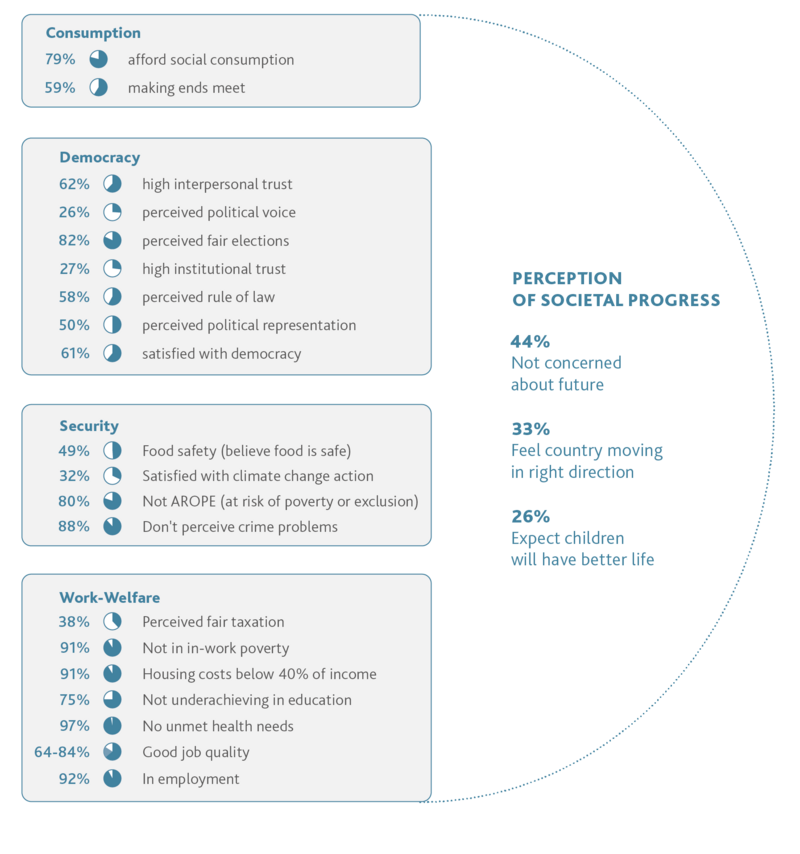

For about half of the indicators in the dashboard, we are able to define a threshold for which one can assess whether the social contract is being met for an individual respondent (for example, they are in employment or they are satisfied with democracy). The figure below shows the proportion of the European population for each indicator for which this is the case.

Figure 2. Proportion of the population for whom the various elements of the pacts are upheld.

Several notable results should be highlighted here.

1. The situation is bleak for the three indicators used to assess the ability to look positively toward the future. A majority of Europeans believe that their country is not moving in the right direction, that their children will not have a better life than they do, and that economic insecurity is increasing for them and their children compared to the previous generation. These cross-cutting indicators highlight what the current social contract can do, and this is a clear warning sign.

2. Democratic Pact: procedures that work... but do not produce the expected results. While a large majority of Europeans believe that elections are free and fair and that the law is the same for everyone, only a minority feel represented by the political sphere, feel they have a political voice, and trust national institutions.

3. Security Pact: an image that differs from that reflected in political debates. Few Europeans say they face insecurity in their place of residence. However, many consider that foods containing chemicals are dangerous for their health and the environment.

4. A central Consumption Pact. As reported in the historical study, this pact has become increasingly important for both governments and populations. Unsurprisingly, driven by a certain economic momentum and the availability of cheap goods made possible by globalization, the indicators are generally positive. However, it should be noted that we could not find Europe-wide indicators equivalent to those existing in France that reveal the other side of the pact, also highlighted in our qualitative survey, i.e. the pressure exerted by consumerist logic. Finally, the satisfaction derived from this pact does not seem sufficient to project a positive outlook for the future (see bullet point #1), as it is so dependent on a precarious balance between income and the cost of living.

What are the disparities within Europe?

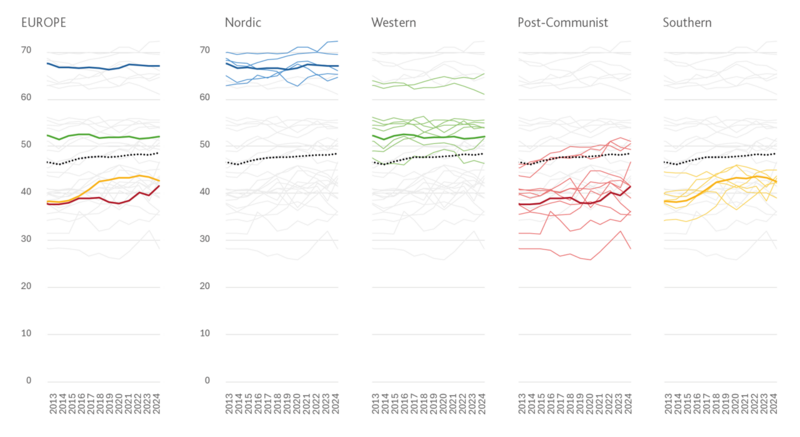

The first finding is positive, as the dashboard shows clear convergence between the four groups of countries in our study: a strong catch-up by the former Soviet bloc countries since the early 2000s and a post-financial crisis rebound by Southern European countries. This has been made possible by improvements in Consumption and Work Pacts, notably through a decrease in the number of people reporting that they cannot make ends meet, in the unemployment rate, and in the number of working poor.

Figure 3. Evolution of the different groups of countries.

Note : A score of 50 can be understood as the European average for that pact for the reference year 2022; for certain indicators, the dashboard data can be used to describe the trajectory since the 2000s.

We then see a clear hierarchy: the Nordic countries clearly score highest, followed by Western Europe, and then the former Soviet bloc and Southern Europe. The most powerful countries in Europe do not fare particularly well: Germany is 13th, Great Britain 17th, and France 19th (out of 31).

How has the social contract evolved over the last 10 years?

Among all the changes, let's focus on three dimensions.

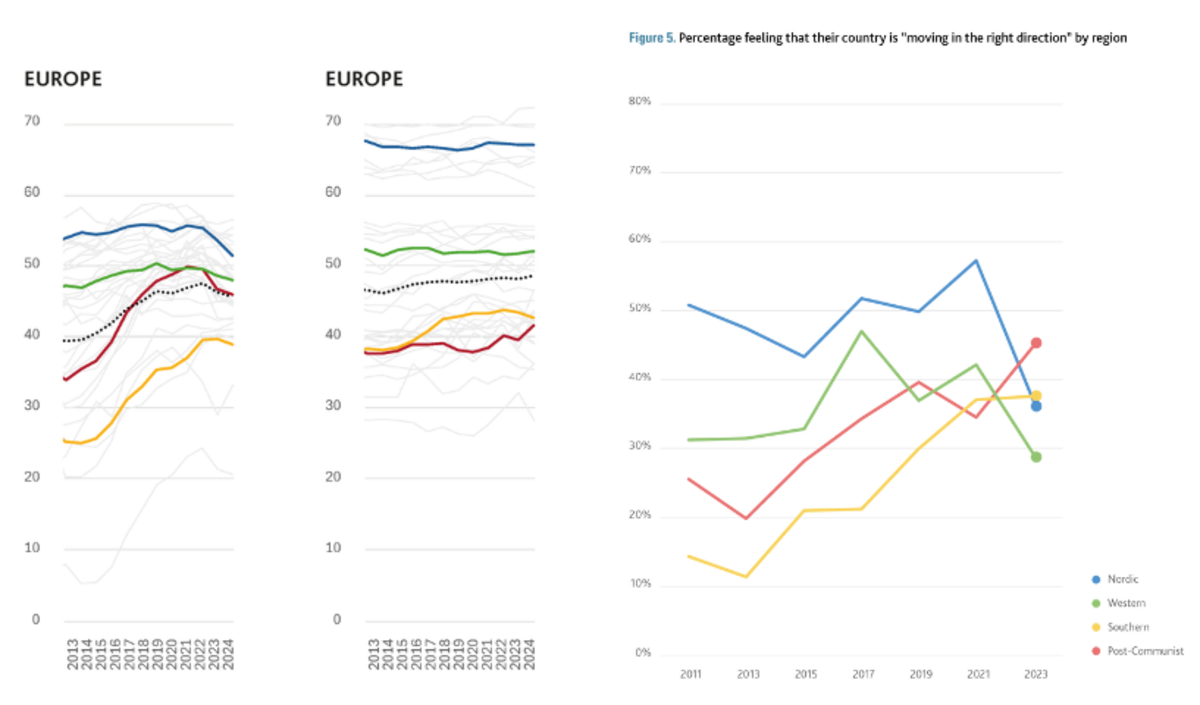

Figure 4. Evolution of the Work-Welfare State and Democracy pacts; percentage of the population who feel that their country is moving in the “right direction”

A Work-Welfare Pact that has been weakening in all four groups since 2021.

First of all, Figure 3 shows rather positive results for this pact : This pillar of our social contract still stands. But on closer inspection, nuances emerge that may constitute weaknesses. For example, while a large majority of Europeans report good quality of work (meaning, recognition, autonomy), one-third of Europeans still feel that they do not receive enough recognition or have enough autonomy. Furthermore, the education indicator reveals that education is deficient for 25% of students, which calls into question meritocratic promises. We then see in Figure 4 a decline, which coincides with the post-COVID period and can be explained in particular by a decline in autonomy and recognition at work, an increase in the proportion of working poor, and a decline in the satisfaction of health needs in many countries. At the same time, there have been only few notable improvements in the other indicators of this weakened pact, which must be the subject of renewed attention in the European project.

A Democratic Pact in “standby” mode.

Northern and Western countries show no progress on this pact, while Southern countries and the former Soviet bloc show limited progress. This is in line with the conclusions of our historical study.

A social contract based on social progress... that has broken down.

Figure 3 shows stagnation (albeit at a high level) for Northern countries and near stagnation for Western European countries. Figure 4 shows a break since 2021 for these two groups in terms of the feeling that they are moving in the right direction. This situation means a lot, given that the idea of progress and advancement has been rooted in the social contract since the post-World War II period. As for the countries of the South and the former Communist bloc, this indicator reflects progress in Consumption and Work-Welfare Pacts.