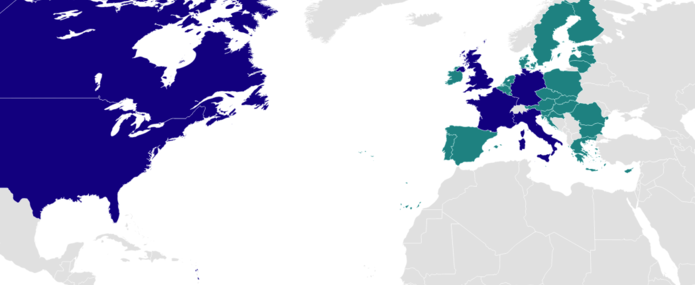

The G7 is a strange exercise: while this club of “historic” powers created in 1975 represents around 45% of global GDP, it is no longer representative of current international power relations, with the main “emerging” countries (China, India and Brazil) being absent. The French Presidency has nevertheless succeeded in keeping the international community's attention on environmental and climate issues. Through sectoral agreements, through the announcement of new contributions to the Green Climate Fund, but also by addressing the link between trade regulation and sustainable development, the Biarritz G7 has made it possible to renew the progress of such a plurilateral body.

Setting a critical agenda

The G7 is today an increasingly problematic club: while its members were once seen as being able to gather around common values of liberal democracy, the heads of these States instead show their disagreements and conflicts, sometimes even around these issues of democracy. In this context, the French Presidency has undeniably succeeded in taking advantage of this political attention to put a series of initiatives and discussions onto the agenda, despite these differences. One month prior to the New York United Nations summits, which will deal with climate, Sustainable Development Goals, and sustainable development funding, how are the G7 announcements more than a taster of what will be officially discussed among all countries on the planet? Several key elements justify the importance of this particular moment.

Firstly, the French Presidency’s insistence on keeping together initiatives on the ocean, biodiversity and climate, at a time when these three subjects have entered into decisive negotiation phases, and where the necessary transformations in sectors such as food, must consider these three issues together and not separately.

Secondly, it was expected that the G7 countries, the main development aid donors, would clarify much more explicitly the nature of the partnership they wish to offer to Africa, in light of the projects and interventions of major emerging countries such as China.1 This was the objective of the invitation, which extended to several African Heads of State, and the announcement of an initiative on female entrepreneurship in Africa was an important step. However, we can consider that the G7 countries, particularly the European countries, still have much further to go in the formulation of their project with and for Africa, especially regarding the African Continental Free Trade Area. 2

Thirdly, the French Presidency’s management of the agenda and political developments has put the issue of the link between the regulation of trade and sustainable development at the heart of the debate and media attention in an unexpected way, given the difficulty of approaching these topics with a US administration that flies solo in this area. By seizing the media focus on the exceptional intensity of the Amazon fires, the French Presidency announced its intention to block the agreement between the European Union and Mercosur,3 putting the climate, along with the trade issue, at the heart of the agenda in a much more critical way than could have been expected. And while this possibility of a blockage may have exerted only very weak pressure on the Brazilian president, this does not take into account the commercial relations with consuming countries, particularly in the European Union: environmental ambitions for all countries throughout the world could be achieved through trade relations, which has been highlighted by this G7: it seems that the Brazilian agri-food sector is relatively more sensitive than the Brazilian President would lead us to believe.

Announcements to be implemented

Environmental issues, particularly making the Paris Climate Agreement a reality, therefore represented one of the five priorities of the G7. Prior to the New York climate summit on climate ambition (23 September), and following a Japanese G20 that was nearly silent on these issues, the summit came at a key moment to seal political commitment. Ultimately, the G7 missed an opportunity to send a unified signal of support to the UN Secretary General who was present in Biarritz: climate issues were not mentioned in the final declaration of Heads of State, although this is hardly surprising given the US position on climate (the US however signed the Metz Charter on Biodiversity, even though they did not ratify the Convention on Biological Diversity). The Biarritz Chair’s Summary on Climate, Biodiversity and Oceans, however, refers to the objectives and processes of the Paris Agreement, notes the commitment of some countries to raising their climate contributions, and mentions some notable advances.

Among these advances, in addition to an action plan presented by France and Chile for the Amazon, the main positive point is the announcement of new contributions to the Green Climate Fund from France, the United Kingdom (expected to co-organise COP 26 with Italy) and Canada. Only France and the United Kingdom have announced an amount equivalent to a doubling of their contribution in line with the wishes of the Green Fund, as Germany and Norway did before them [press release]. The G7 has also led to many voluntary commitments, supported by States (such as the Metz Charter on Biodiversity) or industries, or a combination of both, on issues as varied as efficiency in the cooling sector, the decarbonisation of the international maritime sector, the ecological footprint of the textile sector, and the preservation of biodiversity by the agri-food sector.

The Biarritz G7 has therefore led to: innovative announcements on the initiative of a small group of countries, the implementation of which will have to be monitored; incremental or more substantial progress on certain negotiations in line with current events, that must be followed up to ensure the transformation into actual agreements; and the inclusion of new topics on the agenda, some more anticipated than others, focusing on the latest headlines.

The French presidency of the G7, praised in France but criticised in the international media, has apparently used all of the possible levers made available by this type of meeting. This G7 clearly demonstrated that, if strategically piloted, such multilateral meetings can lead to certain types of agreement and pressures exerted on each party, serving as a deterrent to taking action in isolation, which obliges, at least to a certain extent, the consideration of our common destiny.

This blogpost has also been published on DIE-German Development Institute website

- 1https://www.iddri.org/fr/publications-et-evenements/rapport/comment-les-pays-du-g7-peuvent-ils-contribuer-reduire-les

- 2https://www.iddri.org/fr/publications-et-evenements/billet-de-blog/lentree-en-vigueur-de-la-zone-de-libre-echange

- 3https://www.iddri.org/fr/publications-et-evenements/billet-de-blog/accord-ue-mercosur-comment-sortir-de-lopposition-entre