In mid-July, the European Commission presented a set of legislative texts reforming the European Union's budgetary architecture for the period 2028-2034. These proposals will be discussed next week by European Affairs Ministers meeting within the General Affairs Council. While the European Commission's previous mandate was marked by the Green Deal, the proposed new budgetary and legislative framework addresses two key priorities for this new programming period, both for the Commission and for Member States: competitiveness and security. Although the environment is no longer a priority on the Commission's agenda, the proposed architecture for the next multiannual financial framework (MFF) does not completely erase the need to address these issues: this blog post presents the main aspects and risks of this new architecture for the financing of environmental and climate measures.

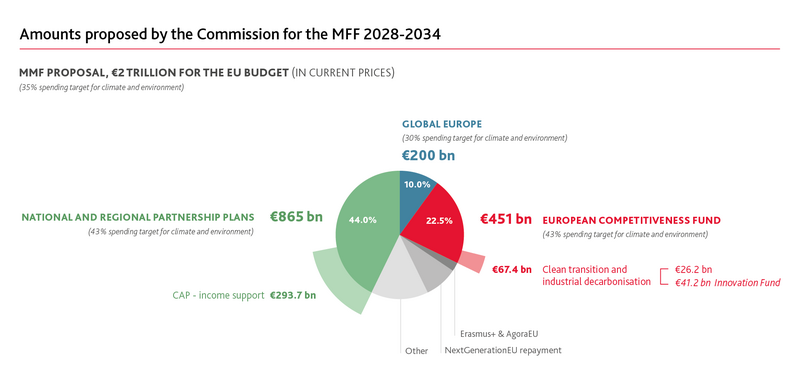

Every seven years, the European Union (EU) adopts a new MFF that sets political priorities and associated budgetary allocations. The 2028-2034 MFF proposed by the Commission is based on three pillars: a single fund bringing together policies managed jointly by the European Commission and Member States, including the common agricultural policy (CAP) and cohesion policy; a European Competitiveness Fund, aimed at strengthening the European industrial base, particularly in the field of defence, and stimulating research and innovation in clean and smart technologies; and an instrument for external actions, aimed at promoting partnerships that contribute “simultaneously to the sustainable development of partner countries and to the strategic interests of the Union.”1 And the MFF’s environmental architecture is largely defined within a single regulation covering all policies financed by the European budget: the expenditure and performance monitoring framework.

An environmental framework that reinforces the mainstreaming approach

The environmental architecture of the European budget is currently based on three levers: (i) two quantified targets defining the share of the European budget that must contribute to the achievement of climate (30%) and biodiversity (from 7.5% in 2024 to 10% in 2026 and 2027) objectives; (ii) the application of the principle of not financing policies that cause “significant harm” to environmental objectives (“Do No Significant Harm,” DNSH); and (iii) a fund dedicated to financing projects in the areas of the environment, climate, biodiversity, and the circular economy (the LIFE program), endowed with a €5.4 billion budget.

The European Commission's legislative proposals for the 2028-2034 MFF are changing this framework. A single target of 35% of the European budget to be earmarked for climate and environmental expenditure is proposed,2 the DNSH principle is harmonized and extended to the entire budget (excluding defence and security expenditure), and the LIFE programme is being discontinued.

In the Commission's proposals, “LIFE activities” are integrated into the European Fund for Competitiveness, within one of its four “policy windows,” i.e. “clean transition and decarbonization of industry,” which aims to support innovative solutions and best practices for the transition, and in the “Facility” included in the Single Fund, designed both to support transnational projects and to assist Member States affected by a crisis. This could weaken the financing of climate and environmental actions, as LIFE activities are competing with other priorities within the Competitiveness Fund and the Facility; on the other hand, some activities that do not fit into a short-term competitiveness approach, such as measures dedicated to biodiversity, may no longer be funded (IDDRI, 2025a).

The Commission is thus strengthening its approach of mainstreaming climate and environmental objectives across the entire European budget–with the notable exception of defence and security spending–at the expense of an approach consisting of dedicated programmes for these issues (climate mainstreaming vs stand-alone climate policies), with the exception of the aforementioned ’clean transition and decarbonization" policy window, which has limited funding. Its budget amounts to €67 billion, of which €41 billion come from the Innovation Fund, which already finances the development of innovative technologies for decarbonization. These amounts should be viewed in the context of both the €451 billion allocated to the Competitiveness Fund and the €2 trillion of the MFF as a whole, and even more so in the context of the climate transition investment gap, which amounts to more than €400 billion per year (IDDRI, 2025a).

The absence of a long-term vision, robust indicators and incentive mechanisms

This framework is only effective if there is a clear strategic vision and robust indicators. However, on the one hand, the Commission does not propose a clear strategic vision, either in the reframing of Europe's external activities, in the proposal for a new Competitiveness Fund, or in the overhaul of agricultural and cohesion policies. This absence is likely to result in approaches guided by short-term political priorities to the detriment of sustainable development. On the other hand, the indicators used to define the achievement of the 35% cross-cutting objective have many weaknesses. A coefficient of 0%, 40% or 100% is assigned to each area of intervention, establishing its contribution to three environmental issues: climate change adaptation, climate change mitigation and the environment. These coefficients are then used to calculate the share of the European budget that contributes to environmental and climate objectives. This allocation is based on an a priori and approximate assessment of the environmental potential of each measure. Several reports have already highlighted the limitations of this approach and the tendency to overestimate the contribution of European policies to environmental objectives.3 This overestimation is accentuated by the fact that, in order to calculate the share of the contribution to the horizontal objective of 35%, the highest coefficient is used.

However, the current proposals do not contain any measures aiming at promoting the financing of measures and projects that are beneficial to the environment and the climate. Under the CAP, for example–which now accounts for 15% of the European budget (although this amount is not final, see IDDRI, 2025b) and concentrates a significant proportion of European funds allocated to the EU's climate and environmental objectives–many mechanisms that promote green measures under the current framework, such as a fully European funding, more advantageous co-financing or the pre-allocation of part of the budget to agri-environmental measures, have been removed. Nor has anything been considered within the framework of the European Competitiveness Fund to ensure that windows providing for investment in health or defence do take decarbonization requirements into account.

The European Commission as the only watchdog for environmental ambition: an architecture requiring reinforcement

While nothing prevents Member States from continuing to finance measures that benefit the environment under the CAP or the Competitiveness Fund, there is nothing to encourage them to do so; on the contrary, the risk of distortions of competition at Community level encourages them to favour other measures. Environmental ambition within the Single Fund is only guaranteed by the Commission through its involvement in the development and monitoring of national and regional partnership plans (NRPPs), the main instrument of this fund. However, this power of control, being unpopular with Member States, could be weakened or even removed during negotiations between the Council and the European Parliament (IDDRI, 2025b). It would then be up to these two bodies to devise other safeguards capable of ensuring environmental ambition in the national plans of Member States.

Similarly, with regard to the Competitiveness Fund, the Commission's proposal remains vague on its governance and the criteria for selecting projects to be funded. These will be specified through the establishment of ad hoc work programmes, adopted by the Commission via implementing regulations. The environmental ambition of the Competitiveness Fund therefore also rests solely on the Commission. Several governance bodies are being considered–a ‘stakeholder council’ and a ‘Competitiveness Coordination Tool’–whose functioning and composition are not detailed in the proposed regulation.

It is now up to the Member States and the European Parliament to negotiate, amend and adopt the texts framing the future budgetary architecture of the European Union proposed by the Commission. During previous negotiations on the 2021-2027 MFF, the European Parliament and the Council succeeded in raising the environmental ambition of the Commission's proposals, via the introduction of a quantified biodiversity target and the earmarking of part of the CAP budget for agri-environmental measures (i.e. eco-schemes). However, the political dynamics within these two institutions have changed and there is no guarantee that they will take the same path this time around.

- 1

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52025PC0551&qid=1753799711782

- 2

This objective is then broken down between the various MFF Funds in Annex III of the expenditure and performance monitoring framework: 43% of expenditure on climate and the environment for the European Competitiveness Fund, 43% for the Single Fund, and 30% for the “Europe in the World” instrument.

- 3

See for instance, Begg, I. et al. (2024). Performance and mainstreaming framework for the EU budget [Study requested by the BUDG Committee]. European Parliament.