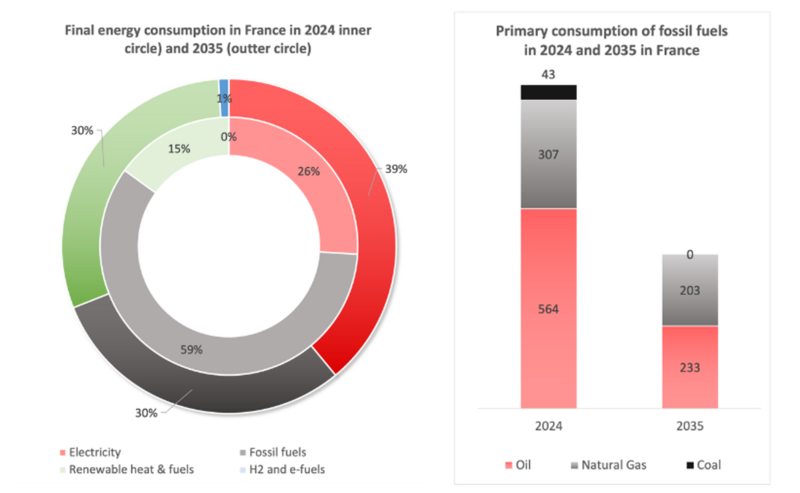

An essential lever for addressing the climate emergency, energy sovereignty, geopolitical resilience and reindustrialization issues, the electrification of uses is at the heart of France's energy and climate strategy. According to the third multi-year energy programme (PPE 3), the share of electricity is expected to increase by 50% in 10 years, halving our dependence on fossil fuels by 2035, with up to €200 billion in savings on the external energy bill.1 Faced with an increasingly significant delay in achieving its targets, the French government has announced the publication of an electrification plan for 2026, which should be finalized after a consultation phase with stakeholders. This blog post identifies several conditions for the successful development of the French electrification plan, covering both governance and substantive issues.

- 1

Estimate based on 2024 data on France's fossil fuel imports (€59.3 billion), assuming stable prices and a linear trajectory of declining oil, gas and coal consumption to meet the 2035 targets set out in the draft PPE 3.

Source : Iddri, données SDES et MTE (PPE 3)

1. Clarifying the political outcome of the consultation process

While the idea of developing this electrification plan in consultation with stakeholders seems relevant from the perspective of promoting collective ownership, it also carries risks. In particular, it risks adding yet another consultation to the already numerous ones carried out as part of France's energy and climate strategy since 2022,2 without being linked to a clearly identified political objective. This should at least take the form of a strategic roadmap with strong political support at the highest level of government,3 ideally combined with strategic objectives and a clear timetable for translating the measures into regulatory and legislative plans.

2. Avoiding fragmentation by establishing a clear framework

To be effective, such a consultation requires precise framing and steering, avoiding at all costs starting from a ‘blank page’, at the risk of opening several Pandora's boxes. This means not reopening the debate on long-term pathways, the exact place of direct or indirect electrification in 2050 or, worse, the electricity production mix issues. All these topics are already covered via the PPE 3, the latest RTE's projected supply estimates and the ongoing review of long-term scenarios.4

The inclusion of a strategic objective for the electrification of energy consumption (possibly broken down by sector) in the PPE could provide a useful starting point for confirming political ambition, in order to focus the debate on implementation. This also implies that the main measures should be identified in advance by government departments, with the aim of focusing collective efforts on defining the conditions for acceptability and success, in order to prepare for future political decisions.

Finally, this process would greatly benefit from a better understanding of the economic impacts of electrification, in order to better assess financing needs, potential benefits in terms of job creation and reductions in external energy bills. But also to show that the increasing delay in electrification has a significant cost for France.

3. Combining short-term action plans with a long-term strategic vision

Given the accumulated delay and the need to accelerate the momentum for electrification, the development of short-term ‘shock’ measures (such as significantly increasing public aid for electrification and overhauling energy taxation) should be the main starting point for the electrification plan. However, in a context of limited political leeway (due to political instability and budgetary constraints), the resources mobilized in immediate response may not be sufficient to meet the ambitions.

It should also be noted that visibility on long-term pathways is essential on many key issues, whether in terms of energy prices, taxation or regulatory decisions with a strong impact on industrial strategies (such as bans on new internal combustion engine vehicles or fossil fuel boilers). In this sense, an electrification plan must necessarily combine short- and long-term approaches, based on detailed implementation planning for different timeframes, together with a dedicated dashboard and monitoring indicators.

4. Developing a new social contract for electrification

Instead of focusing discussions on the main technical and economic issues–which technologies to deploy? At what cost? With what optimization levers?–this process should serve to open up the subject of electrification, by further integrating the issues (and potential obstacles) from a political and social perspective. This transformation can only succeed if electrification becomes a clearly identified and desirable social project, both at the collective level (decarbonization, energy independence and sovereignty, geopolitical resilience) and at the household level (purchasing power, comfort, resilience to price shocks).

Beyond operational measures, this therefore requires significant work to raise awareness and communicate the benefits of electrification in order to improve its appeal. As long as French households fear a surge in electricity prices more than a surge in the price of imported fossil fuels, and as long as the media debate continues to be dominated by the cost of the transition to electricity rather than the (economic, environmental and geopolitical) cost of fossil fuels, and as long as nearly two-thirds of the population believe that electric vehicles emit no less greenhouse gases than combustion engine vehicles, the collective support needed for a change of scale will remain out of reach.

A broader approach to the conditions for successful electrification should, in particular, make it possible to better address several structural issues:

- How can we add a ‘right to electrification’ to a public electricity service that has historically focused on access to low-carbon and domestic energy, guaranteeing accessibility to transition solutions for all, including capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operational costs?

- How can we develop a narrative on electrification that speaks to people, beyond the sometimes overly abstract macroeconomic impacts? How can we develop a pragmatic discourse that highlights the benefits and best practices while recognizing the constraints associated with changing practices?

The social contract approach is an interesting avenue for examining these issues at the sectoral level (cf. mobility [IDDRI, 2025a]). But it is also useful for addressing the–politically sensitive–issue of the conditions for the success and acceptability of new, stringent regulations, taking into account social and economic realities. Indeed, an electrification plan that lives up to its ambitions cannot be limited to incentives. Beyond banning the sale of new internal combustion engine vehicles, this issue also arises in particular with regard to the phasing-out of fossil fuel heating in existing buildings, requiring new regulatory tools and a visible and credible roadmap.

5. Laying the foundations for systemic reform of energy taxation

We are currently experiencing a paradoxical situation: virtually all observers and political actors agree that taxing electricity twice as much as gas or fuel oil is completely inconsistent with the objectives of decarbonization and electrification. But the turmoil caused by the Yellow Vests movement seems to have stifled any discussion of the necessary (and ideally desirable) changes to energy taxation. Yet turning a blind eye to this issue is not an option: despite the freeze on the climate-energy contribution since 2018, energy taxation is already changing, driven by developments in energy saving certificates (ESC) and the extension of the European carbon market (EU ETS) to the building and transport sectors, now expected in 2028.5

In line with the social contract approach, the electrification plan should serve as a starting point for launching an in-depth assessment of the issues, objectives and trajectories for a more systemic reform of energy taxation, in order to make it a central lever of the decarbonization and electrification strategy, as envisaged in the draft reform of the European Energy Taxation Directive and a recent opinion from the European Commission.6

Electrification can indeed not take place without a structural improvement in the competitiveness of electricity vis-à-vis fossil fuel alternatives and without credible guarantees on price (and tax) stability over time, so that the project for the future does not turn into an electrification ‘trap’. In this regard, it should also be noted that citizens are aware of the risk of erosion of tax revenues from fossil fuels linked to decarbonization, fearing a potential transfer to electricity.7

6. Electrification as a driver for a new industrial policy

Electrification is a key challenge for the reindustrialization of France, centred around a number of complementary issues:

- Improving preferential access to low-carbon electricity to strengthen the competitiveness of French industry: with prices below €50/MWh on the wholesale market, France is now one of the most attractive destinations for electricity-intensive industries ;

- Creating the conditions for industrial electrification by providing attractive long-term contracts to manufacturers who choose to electrify, and by putting in place appropriate support and risk reduction tools;8

- Make electrification the driving force behind French and European reindustrialization by fully committing to the race for green industries and technologies in order to counter the decline in investment in cleantech: electric vehicles (including heavy-duty mobility), batteries, heat pumps,9 solutions for industrial electrification, renewable energies, home automation and smart management systems, etc.

On these issues, it seems particularly important to clarify the relationship between the work on the French electrification plan and that of the parliamentary mission on industrial electrification, launched in January 2026.

7. Combining electrification, flexibility and energy efficiency

Another potential pitfall concerns the idea that any growth in electricity consumption is necessarily virtuous, overlooking the principle of ‘energy efficiency first’ and the importance of energy conservation policies, which significantly reduce the need for investment in network infrastructure and means of production.

The relevance of electrification policies will depend on the ability to capitalize on energy efficiency gains10 and ensure that these new uses are levers of flexibility for the electricity system.

This calls for a more systemic approach to cross-cutting issues such as price signals and energy pricing (in relation to the competitiveness of electricity vis-à-vis fossil fuel alternatives and incentives for flexibility), the architecture of the electricity market to support flexibility, and technical standards to ensure that the potential for flexibility linked to new electrified uses is fully exploited.11

8. Opening up on the international scene

Not limiting the discussion to the French case alone and drawing inspiration from international examples is essential. Despite the historical achievements of its electric system, France is now lagging behind and needs to catch up. This means, in particular, examining best practices and recent transformations in other countries, such as:

- The unprecedented growth of the electric vehicle market (particularly heavy goods vehicles) in China, and more generally the rapid electrification of the entire Chinese economy;

- The record reduction in electricity taxation adopted by Denmark for 2026: it was the Member State with the highest taxation (€90/MWh), it now has the minimum rate permitted at European level (€1/MWh), reducing household bills by up to €500;

- Norway's success: electric vehicles now account for 95% of new car sales;

- The implementation of the ‘electricity social bonus’ for low-income households in Spain, which could serve as an example for a similar scheme in France (particularly to offset an increase in carbon taxation);

- The accelerated roll-out of heat pumps in Scandinavian countries (despite weather conditions that are, in theory, less favourable), with up to three times more heat pumps installed per capita than in France;

- The plan to reduce electricity prices by €10 billion announced by the German government, including new preferential access measures for manufacturers, a reduction in taxation (for professionals) and a transfer of part of the network charges to the state budget.

Taking international issues into account necessarily leads to the observation that Europe's energy, economic and geopolitical sovereignty will depend on electrification. The development of the French national electrification plan therefore represents an opportunity to send a strong political signal and assert French leadership on this issue ahead of the preparation of the European action plan for electrification (now expected in the summer of 2026), not to mention the adoption of the Networks Package (IDDRI, 2025b) and the development of the energy and climate framework for 2040.

- 2

Examples include the late 2022 national consultation ‘Our energy future is being decided now’ (including the ‘Youth Forum’), the thematic working groups of the French energy and climate strategy (SFEC) under parliamentary supervision in spring 2023, the late 2023 public consultation on the ‘main guidelines of the SFEC’, the consultation ‘Planning a carbon-free France’ on the revision of the national low-carbon strategy (SNBC) and the PPE, followed by a new consultation on the draft PPE 3 between March and April 2025 and the publication of the draft SNBC 3, which should again be subject to a "final public consultation via electronic means" and opinions from advisory bodies. Not to mention the consultation initiatives carried out in parallel by the General Secretariat for Ecological Planning (SGPE) (in particular the regional COPs) and the numerous working groups organized by the Directorate-General for Energy and Climate (DGEC) as part of the development of SNBC 3 and PPE 3.

- 3

This support may come from the Matignon green cluster and the SGPE, or through the appointment of a dedicated interministerial coordinator.

- 4

Several major long-term scenario exercises will be reviewed ahead of the 2027 national elections. This is the case for RTE's ‘Futurs 2050’ scenarios, but also for the long-term scenarios of Ademe, négaWatt and the Shift Project. Not to mention that modelling work ahead of the fourth revision of the SNBC and the PPE (which is scheduled to be adopted in the summer of 2028) should normally begin now.

- 5

Not to mention the 25% reduction in the transmission tariff contribution (CTA) announced by the Minister of the Economy, Roland Lescure, at the very beginning of 2026.

- 6

The European Commission is currently developing ‘recommendations on electricity taxation in connection with the action plan for affordable energy’. It encourages Member States to completely eliminate taxes on electricity for households and reduce them to the legal minimum (€0.5/MWh) for businesses, to ensure that electricity is systematically taxed less than fossil fuels, and to reduce the VAT rate on electricity.

- 7

With three-quarters of energy tax revenues coming from fossil fuels (mainly oil), the decarbonization trajectory could lead to a rapid erosion of taxed volumes and tax revenues, as illustrated by the Directorate-General of the Treasury in its work on the economic challenges of carbon neutrality. An IDDRI project involving focus groups with citizens confirms that they have clearly identified these developments and the associated risks.

- 8

Beyond direct investment aid, this could include carbon contracts for difference or public guarantees to pool the risks associated with carbon price volatility.

- 9

Beyond the market for individual heat pumps, which is already well invested in via the target of producing one million heat pumps in France each year, it will also be necessary to invest in the future markets for industrial heat pumps and systems adapted to multi-unit buildings.

- 10

For example, one MWh of electricity used in heat pumps or electric mobility can replace two to three MWh of fossil fuels.

- 11

This involves, for example, considering regulatory standards that would ensure that all new electric vehicle charging stations and heat pumps installed in new (and therefore well-insulated) buildings can be controlled according to economic or technical signals, in order to fully exploit their flexibility potential.