On November 11, the German Government finally adopted its long-awaited 2050 Climate Protection Plan (English summary here). The adoption of the plan is the fruit of a 2 year process of technical development, intensive public consultation and ministerial disagreement over sector targets in 2030. However, thanks to a last minute deal, Environment Minister, Barbara Hendricks, now has a 2050 plan (including sector targets for 2030) that she has taken to COP22 in Marrakech to signal Germany’s commitment to the Paris Agreement. What should we make of Germany’s new plan?

What does the plan say?

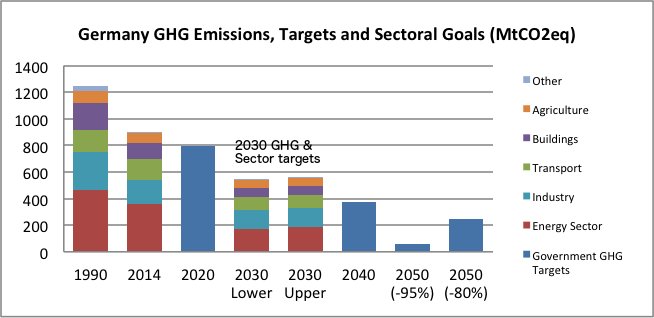

The Plan sets out a broad strategy to achieve Germany’s existing goal emissions goal of -95% on 1990 levels by 2050. It thus presents an outline of the necessary transformations required in each major emitting sector of the economy – i.e. buildings, power, transport, industry, land use, etc – in order to achieve that target. It also it starts to translate these sector transformation strategies into short term target ranges and measures. For instance, targets are set to reduce emissions by 2030 in buildings (-66-67%), in energy (-61-62%), in industry (-49-51%), in transport (-40-42%) and in agriculture (-31-34%), all compared to 1990 levels. The kinds of measures that will be needed to make these targets happen are also listed, e.g. scaling up incentives for deep and staged energy retrofits in the building sector, ensuring that most new cars are electric by 2030, environmental tax reform, reducing nitrogenous fertilisers, etc. While 2040 and 2050 targets for individual sectors are not given, the plan indicates the broad direction of travel out to 2030 and beyond by setting out key principles for action, as well as some important practical steps for preparing these goals. Many of these measures are very positive and consistent with insights and recommendations that have emerged from “unofficial” 2050 decarbonisation scenarios for Germany, such as those presented in the Deep Decarbonisation Pathways Project. The German 2050 plan also acknowledges the need to speed up progress on the domestic transition compared to its current trajectory, as IDDRI has recently noted is the case both for Germany and the EU as a whole.

Source: IDDRI, based on data from (BMUB, 2016) Klimaschutzplan 2050; German Federal Environment Agency

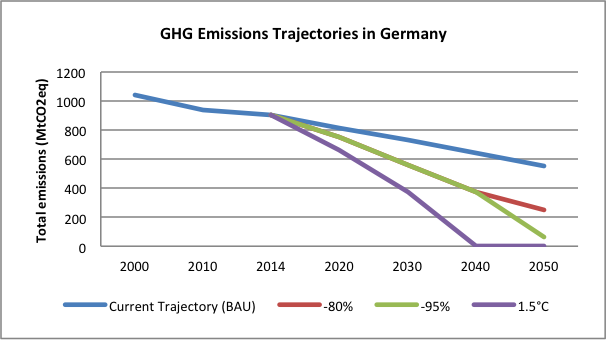

Source: IDDRI, based on data from (BMUB, 2016) Klimaschutzplan 2050; German Federal Environment Agency

At the same time, the plan is noticeably silent on some important issues that will need to be resolved if Germany is to achieve it 2050 objectives. For instance, a decision to phase out coal-fired power well before 2050 was removed from the final draft of the plan. Transport targets for 2030 have been watered down due to industry pressure. The plan also says little about how to incentivise Germans to make some important behavioural changes, like to eat less red meat. Further, despite doing its best to be consistent with global action to achieve the “below 2°C” target, the plan admits to being inconsistent with aim of 1.5°C introduced in Paris (see Graph).

Source: IDDRI, based on data from German Federal Environment Agency

Source: IDDRI, based on data from German Federal Environment Agency

What does the plan mean for German climate policy?

For Germany itself, the plan is an imperfect tool to achieve its aims, but it is unquestionably a big step forward. As noted, there are still contradictions between what the plan says is necessary and the specific actions that are proposed, and more quantitative detail on individual sector transitions beyond 2030 might have been desirable. But these weaknesses of the plan also need to be put in context. Part of this context is a rapidly approaching German federal election in September 2017. But more importantly, one planning exercise cannot be expected to resolve all of the social, economic and political issues that need to be tackled to completely decarbonise an economy as large as Germany. On the contrary, such exercises kick start and structure a process for resolving these issues, as explained in a recent IDDRI paper on lessons learnt by the DDPP teams. If judged on these terms, the plan gives reason for optimism.

- First of all, the plan follows roughly 2 years of intensive analytical work, national debate and public consultation about the way forward for national climate policy. This gives policy makers a fairly solid basis for implementing the orientations, targets and measures that are already in the plan.

- Second, the process has identified some important political economy challenges to implementation, but it has also put the focus of these policy debates squarely on the right issues. For instance, while a plan for coal power phase out is still missing, the government has acknowledged the need develop regional industrial transition plans for lignite mining areas as a first step. So, one can see how the results of the planning exercise could set in motion other necessary work that is needed to unblock some of the toughest issues.

- Third, the plan acknowledges its own short-comings and, thus, it will be revised every 5 years, in line with the ambition cycles of the Paris Agreement. The option of exploring the implications of 1.5°C is also not precluded by this plan, which has no legal status. Room has intentionally been left for improvement. Future revisions will be informed by some new governance arrangements that should help to strengthen the plan over time. These will include a strengthened role for independent advisory committee in advising successive governments and a new structural change commission.

What does the Plan mean for the Paris Agreement?

Despite its imperfections, Germany’s 2050 Plan is a genuine display of commitment to honouring the Paris Agreement by Europe’s largest economy. It is also a timely reminder that the Paris process is bigger than one US election. However, for Germany’s commitment to continue to be meaningful, some other things need to happen. First, Germany will need to continue to improve on the weaknesses of its 2050 plan – and relatively quickly. For example, if Germany cannot agree to phase out unabated coal plants well before 2050, then it will be hard to maintain arguments that much poorer countries should do likewise. Further, Germany’s commitment to Paris could quickly seem meaningless if other countries do not follow up with their own (serious) 2050 plans. Other countries in the EU, in particular, need to follow suit. But make no mistake, this is no easy task. Indeed it is not meant to be: the main value of a long-term plan is to make explicit the hard choices to be made, the trade-offs and the benefits, as the German experience shows. Getting serious about this longer term strategy making exercise is urgent for all countries.