[SDGs Series N°3] Following an initial overview of government and NGO initiatives related to SDG implementation, this blog post explores the reasons why some businesses are already taking an interest in them, and why the rest should do the same.

Over the last two decades, businesses, which are key players in sustainable development implementation, have progressively become associated with the major international cooperation discussions on this subject. The SDGs adopted in September 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly are part of this dynamic: businesses have participated in the negotiations on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and their input has been explicitly requested (Articles 41, 52 and 67). One year after the entry into force of the SDGs, the mobilization of businesses is beginning to take shape. According to a survey conducted in 2016 among more than 2,000 professionals, half of the multinational companies have planned to commit themselves to the SDGs. In France, a quarter of CAC 40 companies mention SDGs in their latest sustainable development report.

What can SDGs bring to business?

One of the arguments generally put forward in the grey literature is that of trade opportunities: the SDGs would constitute a kind of agenda for the economic opportunities of tomorrow, beyond those sectors that are usually involved with energy transition. These opportunities are difficult to quantify, but indicate a growing understanding among companies that it is in their own interests to contribute to a more sustainable and fairer society and an awareness of what transformations in their activities will be necessary to achieve this. However, these transformations will lead to significant reallocations in terms of employment that must be supported by the public authorities. Moreover, the time lag between investment and return can be very long in some cases, which may be an obstacle in an entrepreneurial context, where businesses are accustomed to short-term profitability. SDGs also provide a key to interpret sustainable development in the form of objectives and indicators for companies to assess their performance in terms of social and environmental responsibility. The reports of the Global Compact (SDG Compass), the Business Call for Action and the Global Reporting Initiative provide toolkits for using this key: impact measurement, definition of objectives, progress monitoring, reporting, etc. What will be the additional contribution of SDGs compared to CSR approaches? Will they encourage companies to take account of new dimensions of sustainable development which have so far been ignored? And to set objectives on themes that are not at the heart of their activities? In any case, the specificity of the SDGs is due to the legitimacy given to them by the UN framework and their adoption by all the world’s heads of state. Those who are sensitized or responsible for sustainable development issues can use this legitimacy internally to convince their managers and also their colleagues to engage in an assessment of their impacts or to strengthen the existing procedures. It is this legitimacy of the SDGs which, according to the companies we encountered, is today their main asset. Finally, SDGs could constitute a common language between a business and its stakeholders: public authorities, suppliers, trade unions, NGOs, consumers, etc. If this common language is then translated into a common evaluation grid, then a supplier would need to observe the same criteria whether that supplier is a client of a private company or a public entity (government, local authority). Could SDGs become established as a common assessment standard?

What roles can other actors play to mobilize businesses?

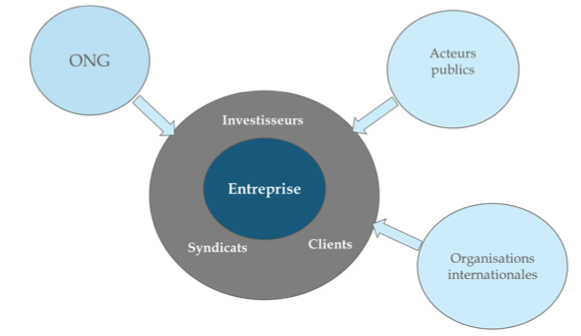

The mobilization of a company in favour of SDGs can also be reinforced by third party actors, first and foremost those who are part of its direct ecosystem: clients, suppliers, trade unions and financiers. For example, the integration of SDGs into extra-financial rating systems can be a powerful lever of influence, similarly their integration into the purchasing standards of client companies can influence the downstream chain. Public actors (state and local authorities) also play an important role, both as regulators - for example, the potential reporting obligations on SDGs - but also as clients of companies. Moreover, public powers can play a facilitating role by organizing exchange platforms with businesses and other actors to stimulate companies to make commitments. This role of facilitating and exchanging good practices between companies is also ensured by initiatives or organizations at the interface between businesses and sustainable development: the UN Global Compact, The UNDP Business Call to Action and the WBCSD. Finally, NGOs and civil society in general can push companies to commit to the implementation of Agenda 2030, through advocacy campaigns and possibly through the use of SDGs to make comparisons and rankings of businesses, in the same way as the Sustainable Development Solution Network (SDSN) has been able to do for countries. Since the SDGs encourage synergy between the different sectors of the community, it is possible to imagine that anti-poverty NGOs could associate themselves with those working on environmental protection under the banner of SDGs to carry out such actions.

Role of the various stakeholders and examples of levers to mobilize businesses

| Stakeholders | Examples of mobilization levers |

| Clients, consumers | Purchasing Behaviours |

| Investors | Extra-financial rating |

| Public actors | Reporting obligation Evolution of criteria for the award of public contracts |

| International organizations | Production of guides and implementation tools Facilitation, exchange of good practices |

| NGOs | Advocacy campaigns International classification of multinational companies |

Companies therefore have good reasons to take an interest in SDGs, firstly for internal reasons (searching for new markets, differentiation, etc.) and secondly because many actors will potentially push them to do so. This mechanism that is both internal and external to the company will nevertheless only really “operate” if SDGs are given prominent media attention, if they are mobilized in the discourses of politicians and NGOs, if they are integrated into evaluation mechanisms, etc. The speed at which this occurs and the levers that will initiate this dynamic are likely to differ from one country to another: in countries where NGOs are well structured, the reputational lever is likely to be decisive. In others, public actors will have an important role to play, particularly through regulatory leverage. (3rd and last article of the SDGs trilogy).