COP16 finalized in Rome at the end of February, after months of postponement following the interruption of negotiations in Cali, to adopt several landmark decisions on the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Framework (GBF). Reaching an agreement on biodiversity financing was a challenge, as this issue is a major source of tension. However, the negotiations resulted in a constructive compromise. How was such an agreement possible? What does it tell us about the collective roadmap for biodiversity in the coming years?

A COP under pressure but holding its ground: behind the scenes of an agreement

The atmosphere in the follow-up to COP16 in Rome was marked by palpable tension, fuelled by the fear of seeing the negotiations fail once again, after the disappointment of the last few days in Cali and in the context of Donald Trump's multiple attacks on international cooperation in the field of sustainable development (withdrawal from the Paris Climate Agreement, suspension of USAID, etc.), even if the United States is not a Party to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Failure would have deprived the international community of the progress needed to implement the 2030 global framework adopted at COP15 in 2022 and of an ongoing dialogue until COP17, which will take place at the end of 2026 in Armenia and will mark the global mid-term review of progress and shortcomings with a view to 2030. The stakes were therefore high, as was the need to preserve a minimum of multilateral cooperation in an already fragmented global context.

The Colombian presidency played a central role, increasing the number of upstream and on-site consultations and encouraging the organization of coordination meetings by groups of countries. For the first time at the CBD, the BRICS group, led by Brazil, structured its positions and proposed concrete solutions. Thanks to its presidency of the BRICS in 2025 and that of the COP30 on climate at the end of the year, Brazil supported the Colombian presidency. By proposing an alternative text, it helped establish a basis for compromise between developing and developed countries. And rather than getting caught up in the logic of opposition, all the players showed a willingness to move forward, regardless of who initiated the proposals.

The trade-offs which were reached in Rome enabled decisions to be adopted on several key issues: biodiversity financing, the modalities of the global review and indicators, as well as cooperation with other international organizations dealing with the environment and development. On the issue of financing, countries agreed to sequence the way in which requests from developing countries are to be met.

This result confirms that despite a very tense international context, progress is still possible when the conditions of trust and listening illustrated above are met, particularly on subjects as complex as financing.

The roadmap to 2030 adopted in Rome

The decision adopted at COP16 on financing is based on two major priorities: on the one hand, mobilizing more resources to achieve the objectives set out in the GBF1, and, on the other hand, organizing the ‘institutional structure’ under the authority of the COP that will manage part of the financial flows for developing countries. This was a key demand of the developing countries, some of which wanted a new dedicated fund to be set up immediately. The compromise reached is based on the adoption of a sequence of decisions to assess what the appropriate institutional structure would be, which could be composed of one or more existing entities (Global Environment Facility [GEF], GBF Fund, Cali Fund2, or others), reformed entities (the reform of the GEF has begun) or future entities (a new dedicated entity).

This work will be informed by the first list of criteria defining the characteristics of this structure, which will need to be refined at COP17. The rest of the process is made up of several millstones: at COP18 (2028), after a thorough review of existing entities and gaps, countries will have to decide whether it is necessary to create a new entity or whether they can adapt the ones already in place. In the event that a new entity is necessary, it will need to be fully operational by COP19 (2030), in order to guarantee effective support beyond 2030.

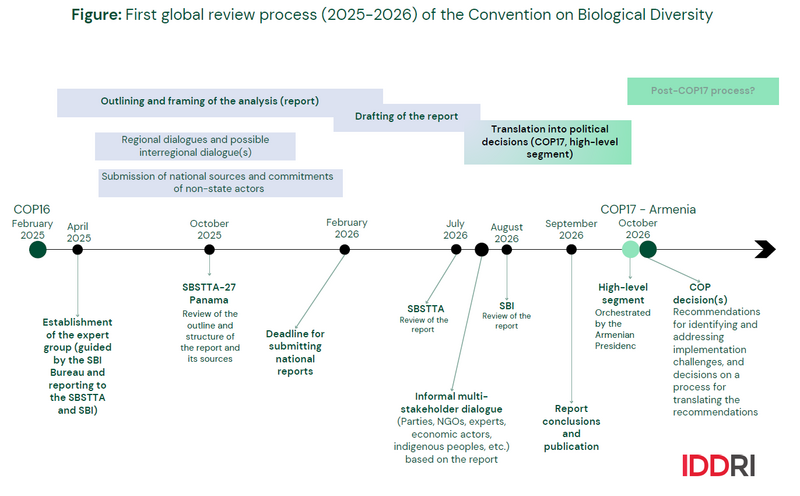

At the same time, several processes are being launched to increase financial resources. One of the thorniest issues, that of broadening the contributor base, will be discussed intersessionally until COP17. In addition, an analysis of the obstacles to biodiversity funding will be carried out, in order to identify concrete measures to improve resource mobilization. This work will be based on a series of studies and reviews focusing in particular on the responsibility of certain financing actors, such as multilateral development banks and the environmental and social guarantees they apply, as well as the synergies between climate and biodiversity financing. The links between debt sustainability and biodiversity financing will also be examined in depth. At the national level, a structured dialogue between the ministries of finance and the environment will be initiated to improve the integration of biodiversity into economic and budgetary policies. Furthermore, COP16 finally adopted a decision specifying the process of the global review: timetable, sources, governance, etc. This review will assess the implementation of the GBF 2050 goals and 2030 targets and also feed into the discussions on financing.

Next steps

While COP16 has brought major advances and clarifications, three major issues are now a priority: better defining the reporting of funding and the evaluation criteria of suitable vehicles, accelerating and strengthening the global review process, and connecting with other key international cooperation bodies.

Monitoring and clarification of financing vehicles

Beyond the increase and the nature of the financing vehicles, one of the main challenges of the coming years will be to ensure transparent and robust monitoring. Work on common methodologies to guide investment decisions and reporting has already begun, between multilateral development banks, within certain countries seeking to better integrate biodiversity into their budget, but also between donors. The challenge now is to anticipate the discussion on these reporting methodologies, clarify their bases, guarantee their disclosure to build trust and allow for an independent review. The challenge is not limited to accounting for flows: it is also about guaranteeing a credible, verifiable evaluation, and ensuring that this transparency is a lever for action to mobilize more funding aligned with needs and supporting actions for biodiversity. It will be necessary to coordinate bottom-up assessments based on the real needs of the countries and several top-down analyses conducted by international institutions or experts3, with clear and up-to-date methodologies.

Discussions on the institutional structure for funding (the Funds) have made it possible to establish essential criteria, but the work has only just begun. It is not just a question of debating a new entity or the reform of the current funds, but of providing precise answers to the real needs of the countries. The list of criteria adopted must be used as a decision-making tool, enabling an evidence-based arbitration and the establishment of a financial architecture that ensures equitable access and real effectiveness of multilateral financing. The functions and principles of the multilateral biodiversity funds identified by IDDRI could inform these discussions.

Global review: speeding up within a tight schedule

The global review has an extremely tight schedule: to carry it out in a credible manner between now and COP17, it will have to rely on the submission of national reports (by February 2026), but also on other sources of analysis to fill the current gaps. There are still too many countries that have not updated their strategies4, and there are gaps in the evaluation of their results. The countries and communities that are the least well-equipped will need support. At the same time, some research must be accelerated and taken into account (technical information will need to be available before October 20255 in order to be included in the review), particularly on the gaps and obstacles to the implementation of the GBF, so that the review is not limited to a snapshot of progress, but also identifies concrete solutions to remove the blockages. To avoid limited political impact, structuring work must also begin now, with additional dialogues to lay the groundwork for the key messages.

Going beyond the CBD

As Colombian Minister Susana Muhamad pointed out, the GBF now has ‘legs, arms and muscles’–but they still need to be used. There will be several opportunities, and they could be used for the finance-environment ministerial dialogue launched at the CBD. On the one hand, the conference on financing for development (FfD4) in Seville in June 2025 and the various discussion frameworks for the reform of the international financial architecture, the successful implementation of the GBF going well beyond the framework of the CBD and requiring the involvement of international financial institutions, public and private actors beyond the ministries of the environment, and multilateral funds that will need to be better coordinated with the needs of the CBD. On the other hand, COP30 in Belém (Brazil) in November 2025 will seek to link climate and biodiversity issues. COP16 laid the foundations for structured monitoring and better organized funding, but without an active presence in these other forums, these advances risk remaining theoretical. It will therefore be necessary to knock on the right doors, starting now.

This work was supported by the OFB (French Office for Biodiversity).

- 1

The GBF adopted in 2022 states that the total biodiversity financing gap of USD 700 billion per year must be closed by increasing resources from all sources to reach 200 billion per year, with a dedicated envelope for developing countries of 20 billion per year in 2025 and 30 billion per year in 2030, and a reduction of harmful subsidies and incentives by 500 billion per year. The COP16 decision specifies objectives and actions (at international, national and private levels) to achieve these global quantified objectives.

- 2

Created before the Rio summit, the GEF is now the main entity acting as a funding mechanism for the CBD and other international conventions; it finances projects in developing countries through the capitalization of developed countries to address global environmental issues by mobilizing domestic and private resources. The GBF Fund, under the GEF, was created in 2023 to support the implementation of the global framework; it aims to accelerate the financing of the Kunming-Montreal objectives by targeting indigenous populations in particular. The Cali Fund is a recent fund adopted at COP16 aimed at mobilizing financial resources for biodiversity from private companies using digital sequence information (DSI). However, it still needs to be structured, particularly by mobilizing voluntary contributions from the private sector concerned.

- 3

Review of existing evaluations: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/publications/2024/oct/bridging-gap-biodiversity-financing

- 4

46 countries have submitted their strategy to date; 125 countries have submitted ‘national targets’.

- 5

For SBSTTA-27, in Panama.