We have known since the 1970s that the Ocean's vast mesopelagic, or "twilight", zone could contain huge quantities of fish. Technological advancements now make exploitation possible and interest is growing—not to provide food, but to be processed into aquaculture feed and nutritional supplements. Yet these fish play a key role in the global carbon cycle and marine food webs, so there are considerable risks inherent in developing commercial fisheries. Scientific knowledge is currently insufficient to support effective management and existing governance mechanisms are ill-equipped to regulate a fishery of such global significance. This blog post introduces the mesopelagic zone and explores some potential avenues for strengthening the international governance framework.

Little light reaches the mesopelagic or "twilight" zone, the waters of the open Ocean at a depth of approximately 150-1,000 metres. Most of the world's fish live there, alongside a diverse range of crustaceans, cephalopods and gelatinous zooplankton ("jellies"), yet our scientific knowledge of this vast midwater realm remains limited.

Many mesopelagic organisms make a daily journey through the water column (up in the evening, down at first light), a phenomenon known as "diel vertical migration". This massive migration transfers energy from the highly productive surface waters to the dark depths below and acts as a "biological pump" that locks away huge quantities of carbon.

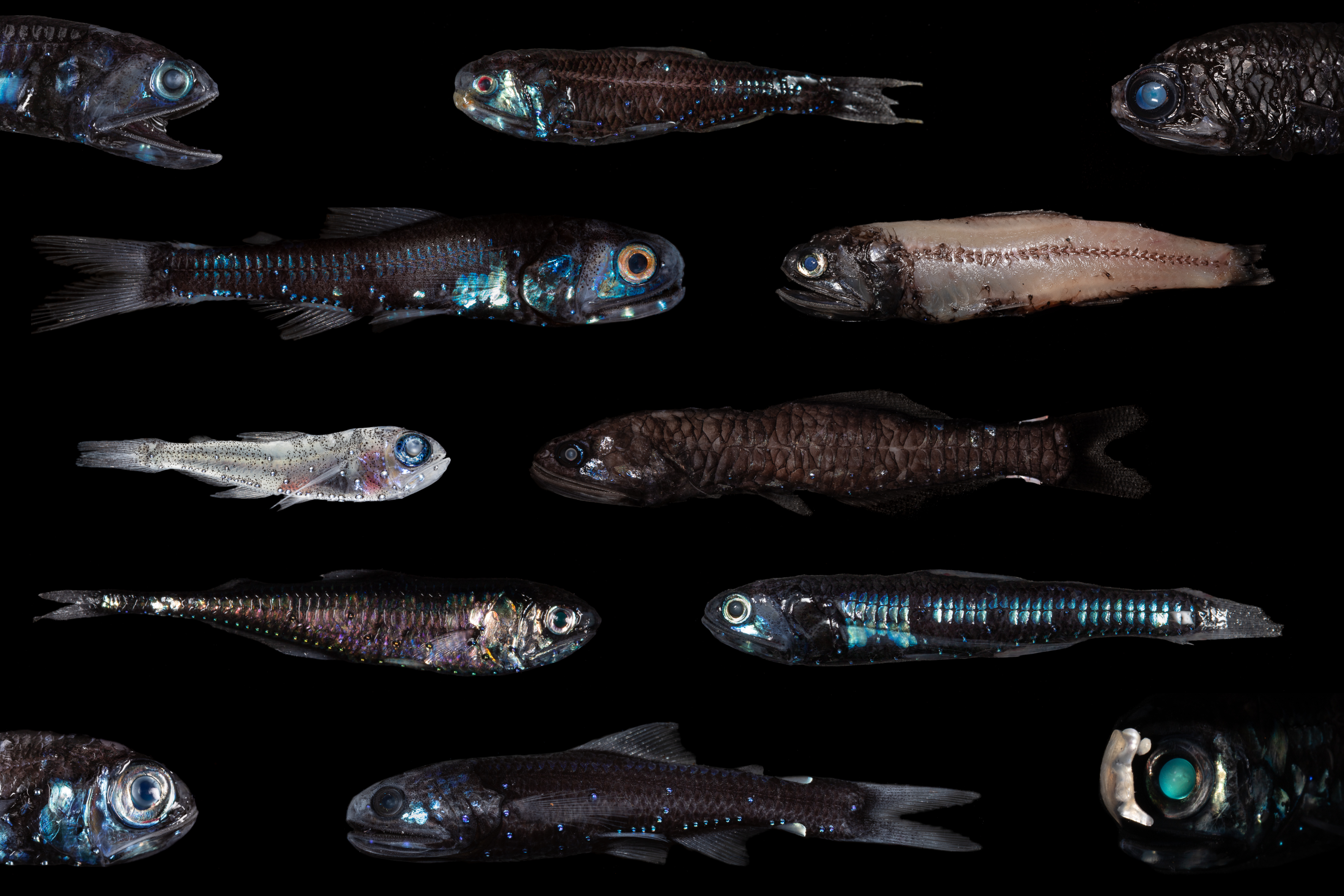

Lanternfish (myctophids), a family of about 250 species of small fish, are particularly abundant. They are a key link in marine food webs, feeding on plankton before themselves falling prey to tuna and other commercially important species.

© Paul Caiger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

The possibility of harvesting these fish has been known since the 1970s but few concerted efforts have been made to exploit them. Not only were lanternfish hard to catch and process, they are unpalatable and may contain harmful toxins. Recent technological advancements have made it easier to catch and process these fish into fishmeal and oils rich in omega 3, so interest is growing in exploiting them for use in aquaculture and nutritional supplements.

Cautionary tales abound in the history of fisheries management, as humans have repeatedly fished stocks to collapse. As mesopelagic species and ecosystems play a critical role in the carbon cycle and marine food webs, mismanagement could have profound global ramifications.

The international community has often been particularly slow to regulate new fisheries on the high seas, i.e. the waters beyond the national jurisdiction of any one country. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982), the "Constitution for the Ocean", accorded all States the right to fish in international waters but included little guidance on how they should discharge their environmental obligations.

The UN Fish Stocks Agreement (1995) provided further detail on how States should cooperate on the management of highly migratory and straddling fish stocks, such as tuna, resulting in the creation of a plethora of Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs). These organisations, essentially groups of States with an economic interest in a fishery, have generally focused on managing a handful of stocks and have long been criticised for opaque decision-making processes and failure to address biodiversity concerns.

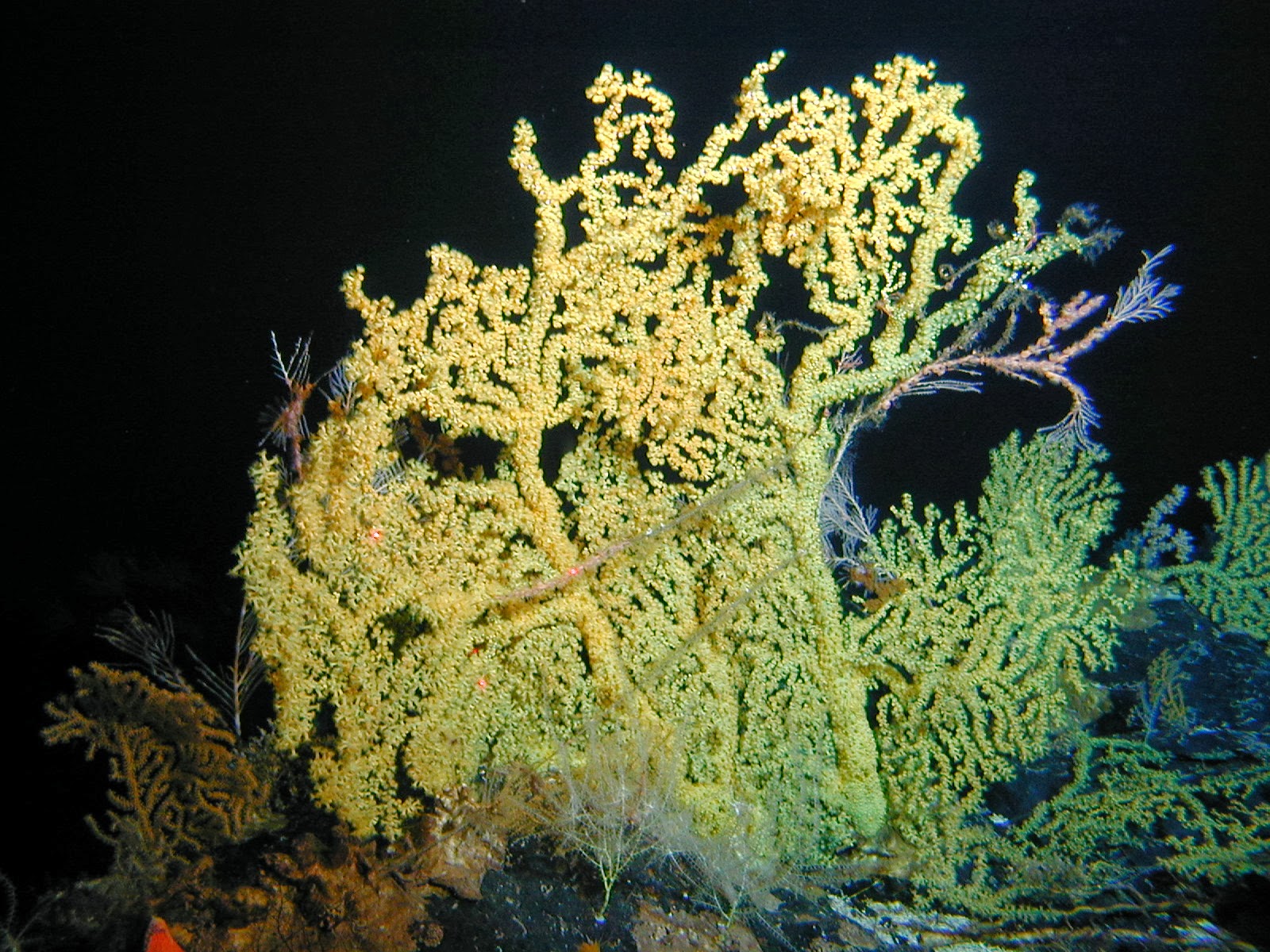

Perhaps most notable is the patchy and inadequate response of RFMOs member States to the repeated calls of the UN General Assembly to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems, such as deep-sea corals and sponges, from destructive bottom trawling. Over 15 years have passed since the UN first called for States to "urgently adopt" conservation and management measures, yet a recent assessment by the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition found that there are still "significant gaps and variability in the implementation of key elements and commitments in the resolutions".

© Hawaiian Undersea Research Lab

International law requires a State to seek approval for a new high seas fishery from the relevant regional management body, but a proposal would not be subject to a thorough environmental assessment, nor would stakeholder have an opportunity to provide input or object. This effectively leaves the governance of mesopelagic fisheries, and the fate of the globally significant ecosystem services they provide, in the hands of a few fishing States.

Negotiations for a new agreement on high seas biodiversity are currently ongoing, providing an important opportunity to reinforce existing environmental obligations and stimulate closer cooperation. The agreement could strengthen the governance framework for mesopelagic fisheries by requiring comprehensive environmental assessments and providing for the designation of protected areas. But the negotiations have been delayed by the coronavirus pandemic and it will be years before an agreement has any impact on the water.

©IISD

A range of scientific projects are underway that aim to shed light on the twilight zone and some deep-sea scientists are calling for a moratorium on mesopelagic fisheries to allow the science to advance before exploitation begins. The Pacific Council, which manages fisheries on the west coast of the United States, has already prohibited fishing for mesopelagic species until they can understand the potential impacts.