In cities, the renaissance of the bicycle, a prime example of a simple technology par excellence, is today encouraging the development and use of a wide variety of digital tools. Many experiments in cities as diverse as London, Lille and San Francisco, are based on the contribution of urban residents through the use of digital tools – a process known as urban crowdsourcing, which was the subject of an earlier post. What benefits can these digital tools bring to the bicycle? What do they tell us about the technical and political challenges of this renaissance? And how does it reflect a new way of “managing” the city? We’ll start with a summary of some of the main elements of the development potential of the bicycle, and the social and environmental gains it represents.

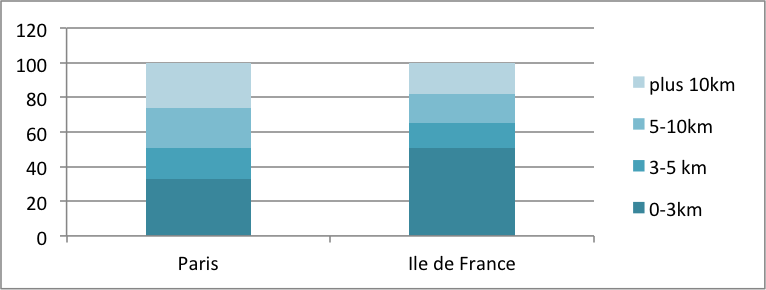

There are numerous ways in which the bicycle can make a substantial contribution to sustainable mobility (zero pollution, providing a beneficial activity for health, low noise, economic feasibility, etc.), which accounts for the ambitious objectives that many territories have set. Large cities like New York, London and Paris, which currently have very low usage levels (modal shares of about 2%), are planning to double or even triple this share by 2020; while more advanced cities such as Strasbourg, Berlin and Copenhagen (8%, 15% and 35% modal shares respectively) intend to continue their efforts. Regardless of the city, the bicycle has a significant development potential. The public policies that structure the entire mobility system are essential here, much more than the usual explanations (culture, climate, topography), which are insufficient to explain the development of cycling, as demonstrated by the work of F. Heran. This potential is illustrated in Figure 1: the distance of car trips made in Paris and Ile de France, which are mainly short journeys, reveals the potential of cycling – the alternative individual and flexible mode of transport.

Figure 1. Distance travelled by car (as the crow flies) in 2010 (Global Transport survey, 2010)

Figure 1. Distance travelled by car (as the crow flies) in 2010 (Global Transport survey, 2010)

What do these bike development policies involve and how can digital crowdsourcing tools contribute to their implementation? Some key elements are presented here, grouped into three non-exhaustive points.

- The development of cycling in cities requires a minimum amount of data on current practices in the territory: what major routes are used or avoided? What are the origins and destinations? How many cyclists are present? These data are necessary from a technical point of view for the purposes of planning, but also from a political perspective to ensure visibility of the practice and to justify possible investment. Data are generally available for other modes of transport, but there is very little for cycling. Several cities are either using or planning to use digital applications to calculate routes that allow GPS tracking (see San Francisco or BikeCitizens). Cities would be able to obtain low cost sets of useful data if cyclists could be motivated and mobilized to use these applications and to generate this GPS tracking.

- The development of cycling requires planning that addresses the needs and behaviours of cyclists. What types of cycling paths are secure and effective? What black spots and gaps persist? What is the requirement for public and private cycle parking in the territory? City leaders cannot satisfactorily answer these questions without the input of inhabitants.

- Firstly, it is impossible to continuously monitor a city territory at a reasonable cost.

- Secondly, it is difficult to gauge the feelings of inhabitants and gain an accurate picture of their infrastructure usage. This socio-technical dimension of change, which has been well documented by social science researchers, can only be obtained through city user feedback.

- Therefore, cities are holding consultations via digital tools for their cycling plans (7,000 participants in the Paris cycling plan); the needs and current infrastructure of cycle parking are to be crowdsourced (pilot project in Grenoble, an example in Washington, D.C.); some associations are developing tools to collectively produce a cyclability map (ADAV), a road traffic security map (New York Vision Zero) and report problems encountered on the roads (2P2R in Toulouse).

- Finally, for these cycling policies to be implemented, it is necessary to convince various city actors, but also to help transform lifestyles. Bicycles usage cannot be tripled simply by the issuing of a decree. The way urban space is distributed between its different uses and the way it is regulated cannot be changed without the mobilization of civil society to overcome the status quo. Digital tools are useful levers. They can give visibility to communities and monitor the desires of the population, for example through participatory budgets where cycling projects are generally numerous and well received (e.g. in Paris) or gamification applications seeking to recreate a positive social standard around the bike. They are also levers and sounding boards for associations, allowing them to see themselves as intermediaries between a community of contributors (which is wider than the circle of activists) and the city. Finally, by making the citizen a contributor and co-producer of the city, these tools are potentially more effective than traditional awareness raising campaigns. They can help citizens to develop an increased sense of responsibility towards the challenges of their city, including the environmental challenges and give visibility to public action. By giving us the ability to conceive different visions of the city (map), to feedback on uses and needs (cyclability map, reporting of problems), to propose projects, the city can “take on board” the citizen as part of its transition movement, by opening a new space for participation, which is possibly more flexible and attractive than traditional participatory spaces.

Finally, facing a transition towards sustainable mobility with issues that are political (games of actors and power), social (an individual does not change alone) and technical (adjusting and building new infrastructure), these digital tools are providing interesting solutions, and revealing new ways for the city to function. The experiments described in this post are generally recent and their level of use by cities has not always lived up to the potential: the technical rationale prevails over the participatory rationale. We are therefore talking here about promises, levers of change, which require time and political will to succeed, as these practices relate to new ways to collectively build the city which will therefore greatly challenge current practices. Despite the contribution from the use of digital tools in terms of simplicity, they are far from being in general usage by the majority of citizens in their diversity.

These innovations through digital technology are just waiting to be seized and tested to enrich our sustainable development public policies!