The 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), under the Chinese presidency but organized in Montreal for health reasons, opens on December 7. The expected objective is the adoption of a roadmap for the current decade–"the post-2020 global biodiversity framework"–aimed at halting the loss of biodiversity by agreeing on a program of actions to "live in harmony with nature" by 2050. A long-term vision (Vision 2050), equivalent for biodiversity to carbon neutrality in the field of climate, in a radical break with current trends. An "opportunity of the decade" for some, a risk of a "Copenhagen of nature" for others, COP15 is being held in a turbulent international context, marked by a global economic slowdown, an increase in inequalities following the Covid crisis, and a war on the European continent exacerbating an already tense geopolitical context, particularly with regard to North-South relations. In this context, what can we expect from the COP15 and from what angle should we evaluate its results? In this blog post, IDDRI proposes a list of 15 key points that will allow us to judge the ambition and credibility of the commitments made by the international community during this event.

A universal framework, recognizing the diversity of regional and national situations

The proposed global framework is based on a "theory of change" founded on the need for a multi-scale strategy involving "all levels of government and society”. While global in scope, its objectives and targets–and more broadly its implementation conditions–are based on the consideration of specific contexts.

1. Adopt a global agreement, imbued with collective ambition and driving sectoral transitions. The global framework for biodiversity will be first and foremost a commitment by the Parties to the CBD to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity, both terrestrial and marine, but also to equitably share the benefits derived from its use. It will include goals and targets for action (see complete list at the end of this post), for which countries will be accountable. However, this roadmap will also have to succeed in speaking beyond national delegations and also embrace subnational authorities, indigenous peoples and local communities, the private sector, NGOs, donors, unions, etc. This global framework defining the collective ambition must be able to be translated into the individual actions of the different actors, which is the only guarantee of a true transition and transformative changes. This is the point on which the previous framework, that of the Aichi targets, stumbled. In this respect, the current architecture of the framework meets this requirement and should therefore not be called into question at COP15.

2. Take into account contrasting contexts and issues. While a global ambition is necessary to act and to commit to a collective responsibility in the face of biodiversity erosion, the roadmap adopted will nevertheless have to be adapted to national circumstances. The 196 Parties to the CBD will thus have to contribute to the implementation of the post-2020 framework by taking into account the specificities of their biomes and ecosystems, the most pressing threats to their territories, but also their means and resources. This is a key principle of the CBD that should be reaffirmed by the global framework, which requires finding a balance between global objectives and means adapted to the diversity of contexts.

An ambition that responds to science's warnings about the main drivers of biodiversity loss

Published in 2019 by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the Global Assessment of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services highlights five key drivers of biodiversity loss: (i) land and sea use change; (ii) direct exploitation of certain organisms; (iii) climate change; (iv) pollution; and (v) invasive alien species. The post-2020 global biodiversity framework will therefore need to contain ambitious targets on all of these factors, at the risk of only partially covering the challenges facing the international community.

3. Driving the transformation of agri-food systems. The IPBES global assessment highlights land use change as the primary cause of biodiversity loss. The agri-food system is particularly concerned here, and the post-2020 framework will therefore have to set a course to refocus its development trajectories. In this respect, Target 7 on pollution will have to include quantified objectives for reducing the use of pesticides and fertilizers and thus encourage the sector to initiate the necessary transformations1 . In the same way, Target 10, which is broader because it concerns agriculture, aquaculture and forestry, should be able to require the structural changes indicated by science. This requires, first of all, a break with the current trends of simplification of agricultural landscapes and crop rotations in many production basins. It also requires taking biodiversity into account as a factor of production: it is on this condition that the evolution of food systems will not privilege short-term productivity at the expense of long-term viability and resilience.

4. Ensuring the political and operational anchoring of the links between biodiversity and climate. The United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), whose COP27 ended last week, is the framework within which states negotiate the mitigation and adaptation policies needed to address a planet that is expected to warm "well below 2°C, while continuing efforts to limit temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”. Although the CBD does not have an explicit mandate on these issues, the links between biodiversity and climate are such that the post-2020 global framework for biodiversity, as a roadmap for the decade, cannot ignore this issue. It is therefore expected, in Target 8 in particular, that there will be an explicit reminder of these cross-cutting issues and the related mitigation obligations.

5. Conserve more and better. Protected areas are now recognized as tools for the conservation and sustainable use of ecosystems and their biodiversity, both terrestrial and marine. A coalition of about 100 countries is now promoting a target of 30% of protected areas and other conservation measures2 by 2030. Target 3 of the post-2020 framework must reflect this requirement, while specifying its qualitative corollaries: management, representativeness and connectivity in particular. The major challenge will then lie in the effective implementation of this key obligation, which will require the mobilization of all stakeholders (intergovernmental organizations, national administrations, indigenous populations and local communities, donors, NGOs, scientists, etc.) and the allocation of dedicated financial and human resources.

6. Driving a global dynamic for ecosystem restoration. The ambition of the post-2020 framework requires not only the setting of conservation targets, but also the launch of a global dynamic for the restoration of degraded ecosystems. This dynamic, with multiple co-benefits (food security, fight against and adaptation to climate change, etc.), appears essential to meet the three objectives of the CBD. Target 2 should therefore be particularly explicit on these issues, contain a quantified objective, and thus fully include the international community in the United Nations Decade for Ecosystem Restoration.

Matching resources to the challenges

A large number of studies3 have been conducted to estimate the financial requirements for biodiversity conservation. Because the models and approaches differ, estimates range from US$ 103 to 178 billion per year for the lower ones, based only on investments to reach 30% of terrestrial and marine protected areas by 2030, to US$ 599 to 823 billion per year for the higher ones. In any case, and beyond the debates on the precise amounts, the global biodiversity framework for the post-2020 period will not be able to ignore this issue and will have to drive a strategy based on an increase in resources, a reform of harmful incentives and a mobilization of a diversity of actors.

7. Restore North-South trust through a financial pact. The increase in funding for biodiversity over the period 2011-2020 has not been sufficient to meet the needs and thus halt the trend of erosion. The post-2020 global framework for biodiversity will therefore have to pursue the objective of closing the gap between the financial means and those needed to achieve Vision 2050. This will necessarily require an increase in financial flows to developing countries, which is the subject of Target 19 and which will certainly be fiercely negotiated. In addition to the amount chosen, this pact should make it possible to re-establish North-South trust and to give developing countries the necessary means to implement the global framework. The rapid release of funds and a constructive dialogue between donors and recipient countries will be essential guarantees for the implementation of the framework.

8. Use existing financial instruments. The outcome of COP27 on the definition of a new ad hoc fund on loss and damage was based on the magnitude of the economic and social consequences of extreme events related to climate change and the need to ensure rapid access to dedicated funding. The adoption of such a mechanism could set a precedent, which will be taken as a reference in the negotiations at COP15. However, the architecture of biodiversity finance has developed differently from that of climate finance. Climate finance is built around a combination of the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the Green Climate Fund, and other specialized funds, while the GEF remains the major mechanism for biodiversity financing and CBD implementation4 . The proposal to create an ad hoc fund for biodiversity does not seem to be the best way to guarantee countries additional resources in the short term and with easy access, and therefore questions its added value and the complexities it could create for recipient countries. Moreover, experience shows that several years are needed between the idea of creating a fund, its establishment and its operational implementation. Therefore, the establishment of such a fund is unlikely to provide rapid and effective support to the implementation of the global framework. However, efforts to improve accessibility to GEF financing and to take into account the particular situation of the most vulnerable countries must necessarily be pursued in order to take into account the legitimate demands of Southern countries.

9. Initiate an internal process assessing implementation needs. At the national level, the mobilization of financial resources is an essential condition for the implementation of the biodiversity framework. Parties will therefore need to determine their needs for the implementation of their National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) through National Biodiversity Financing Plans (NBFPs). These plans will have to identify the necessary amounts, evaluate the available resources and thus highlight possible needs to be met, not only through international flows, but also through possible internal reforms generating new resources; to this end, the BIOFIN approach, which aims to improve national financial systems, could constitute an interesting inspiration. This internal exercise appears to be an indispensable corollary to increasing international flows.

10. Aligning financial resources and flows with the objectives of reducing the factors of biodiversity loss. This is an essential issue of coherence, since the increase in public funding cannot be effective if other financial flows remain aligned with trajectories that destroy biodiversity. It is also a question of increasing the amount of funding available to developing countries. In this respect, many countries remain dependent on biodiversity for their economic development and job creation for a rapidly growing population5 . Private financing must therefore also be part of an ecological sustainability framework and integrate biodiversity as a production factor. Given the magnitude of the amounts at stake and the links between biodiversity and adaptation to climate change, it is also through this approach of redirecting funds towards development that is positive for nature as well as for the climate that the mobilization of multilateral development banks must be considered6 . In addition, and beyond direct and specific financing for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, it is also a question of reforming those that cause damage, first and foremost the so-called harmful subsidies. Target 18 should therefore set precise objectives in this sense and, at the very least, not alter the directions proposed by Aichi Target 37 . More broadly, an explicit reference to the alignment of all financial flows with the global framework will be a key element in sustaining the momentum that is currently emerging, notably through the Task Force on Nature-Related Financial Disclosure (TNFD) and other initiatives in the financial sector.

Robust implementation and facilitation processes

The gap between the ambition of the Aichi Targets 20211-2020 and their implementation results, which are considered very insufficient to halt the ever-increasing loss of biodiversity, can be explained in part by the lack of facilitating processes: weak transparency or accountability mechanisms, no compliance or sanctions regime, no continuous improvement mechanism, and few means to support implementation and build capacity. The development of robust processes, specifically dedicated to implementation issues, is therefore essential to give credibility to the post-2020 global biodiversity framework and ensure its effective implementation.

11. Submit national targets contributing to the collective ambition of the framework by 2023. Parties to the CBD will need to update or submit their NBSAPs, the preferred instrument for implementing the Convention. However, due to the short timeframe for implementation of the global framework (8 years), countries should submit their national targets before the end of 2023. These contributions, aimed at "domesticating" the global targets and triggering early action, should come before the submission of NBSAPs, whose development process requires more time. To do this, it is crucial that the COP adopt a format and guidelines for the submission of these contributions, including the degree of alignment of national targets with global targets, and the identification of financial needs to implement them. The aggregation of these national targets should allow for the assessment of the collective effort one year after the adoption of the global framework.

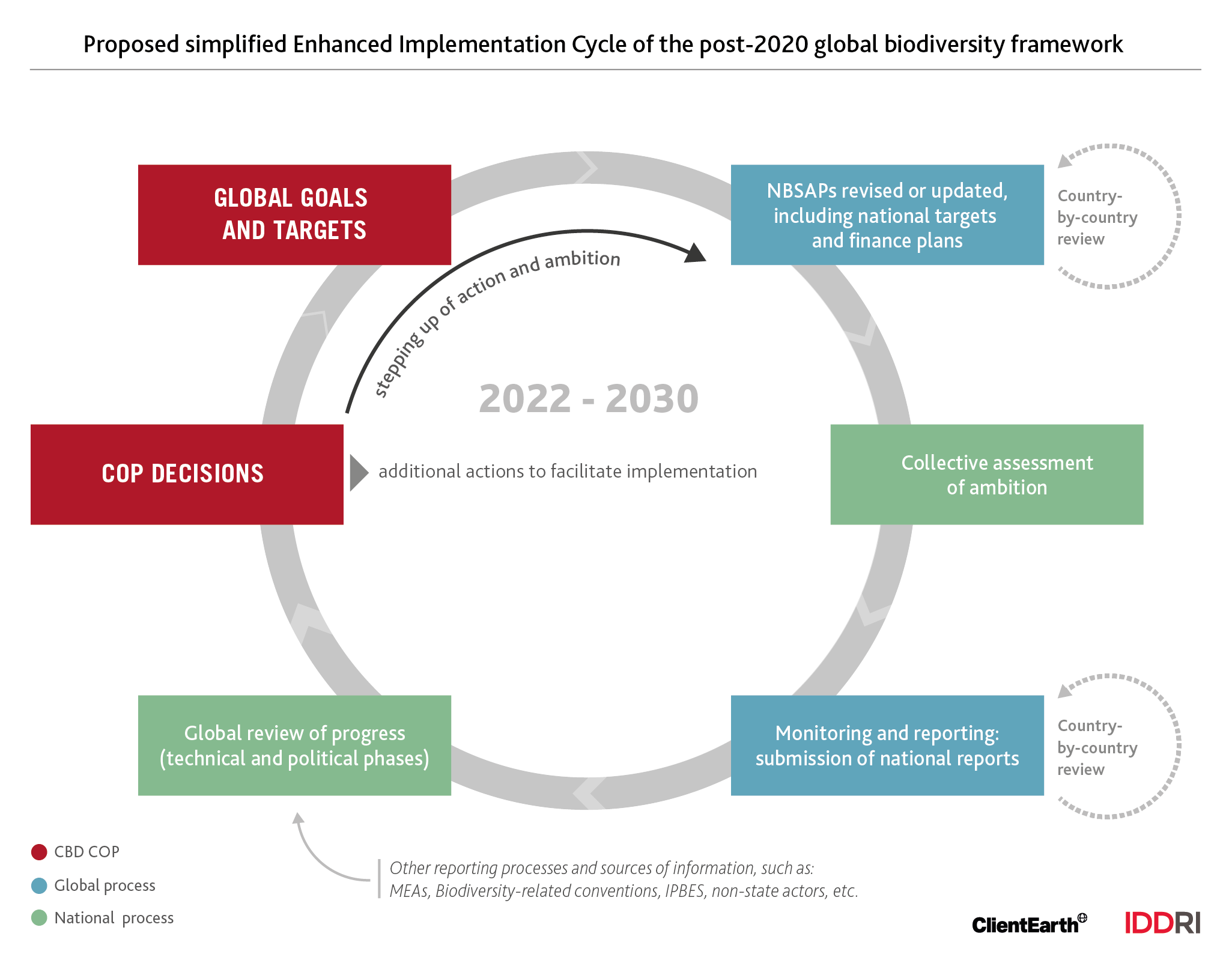

12. Adopt an effective implementation cycle that facilitates ambition and action. More broadly, the planning and alignment of NBSAPs will need to be part of a coherent cycle, which also includes the different elements of implementation, monitoring, reporting, review and acceleration of action. COP15 will need to adopt the principles and components of this cycle, but also establish a dynamic for incremental improvement of these processes. Among the key principles that should guide implementation, it should be emphasized that the processes related to the transparency and accountability framework do not impose additional burdens on Parties, but act as a "support mechanism", especially for developing countries. To best support ambition and action, this implementation cycle should, inter alia: facilitate capacity building and access to finance; adopt simplified reporting formats and tools and timelines synchronized with those of other multilateral agreements; strengthen the collective review of implementation through a global stocktaking to identify gaps and inform possible adjustments; and establish a country-by-country review. These different components should ultimately allow for regular updates on implementation and adjustments to the global trajectory.

A roadmap for all stakeholders

Only a contribution from all stakeholders can ensure the effective implementation of the future global framework, whose adoption will necessarily involve political compromises and tradeoffs.

13. Mainstream commitments into sectoral agendas. The post-2020 global biodiversity framework has the ambition to become the compass of the international community and as such will constitute a comprehensive roadmap. Achieving this global ambition will require each actor to be responsible and accountable for its implementation. Environmental actors–including national ministries and dedicated intergovernmental organizations–will have to adapt their work program and put it at the service of the objectives and targets set. But the challenge also, and perhaps above all, lies in the appropriation of the framework by sectors that have a significant impact on biodiversity–agriculture, fisheries, industry, for example. This will have to be done at the country level (via the ministries in charge and the sectoral representation groups), but also within the framework of the competent multilateral organizations, such as the FAO or the regional fisheries organizations, for example. To do this, the provisions of the global framework will have to be sufficiently precise to allow their operational implementation in these fora.

14. Involving and engaging the whole of society. The fight against the erosion of biodiversity necessarily requires a participatory approach, at all levels and with all stakeholders. In this respect, the recognition of the role of indigenous peoples and local communities, who contribute to its preservation8 , is a requirement emphasized by many States and is now well integrated into the draft global framework (section B.bis, target 21). The private sector has not been left out and companies are explicitly mentioned in Target 15. This is the meaning of the "whole of government/whole of society" approach that inspires the framework, but whose operational implementation nevertheless requires specific provisions. It therefore seems crucial to extend the mandate of the Action Agenda launched in 2018, which allows Non-State Actors to commit to a transformation of their activities, while strengthening monitoring processes to avoid mere "greenwashing"9 .

15. Putting equity at the heart of the global framework. Where there have been recent advances in global environmental governance, they are increasingly conditioned by a balance, if not a reconciliation, between the demands of developed countries and the aspirations of developing countries. Even if this distinction between the two hemispheres sometimes proves to be caricatured, it is nonetheless a marker of current international relations, linked to the blatant asymmetries in the financial capacities to deal with the multiple crises the world has been experiencing since 2020. In the specific context of the global framework, this imposes, among other things, a recognition of a pluralism of approaches to conservation10 . It also requires particular attention to the objectives and targets based on the CBD's "sustainable use" and "equitable sharing" pillars. In this regard, references to development goals (section C, milestone B.2) and food security (Target 9), as well as provisions on digital sequencing information to be adopted by a specific COP decision, will be essential for the agreement to be adopted.

The success of the COP15 is not yet written. Beyond the conditions highlighted in this blog post, we must also hope that the possible technical and semantic disagreements, as well as the ideological postures that have too often prevailed during previous negotiation meetings, will give way to real political discussions–and ultimately to compromises that are up to the task.

CBD’s Main Objectives

A

Conservation of biodiversity: ecosystems’ integrity, extinction rates

B

Sustainable use of biodiversity

C

Fair and equitable sharing of benefits from the exploitation of genetic resources

D

Implementation means

Action Targets

Reducing threats to biodiversity

1

Spatial planning

2

Restoration

3

Protected areas (mainland and marine)

4

Management for the conservation of species and genetic diversity

5

Sustainable harvesting, trade, and use of species

6

Prevention and reduction of invasive alien species

7

Reducing pollution from all sources

8

Minimising climate change impacts

Meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and sharing of benefits

9

Ensuring benefits (nutrition, food secutity, medicine, revenues)

10

Guaranteeing sustainable management of all areas (agriculture, aquaculture, etc.)

11

Maintaining and increasing nature’s contributions to air and water quality, and to the protection against extreme events

12

Increasing area of and access to blue/green spaces when in urban, high-density spaces

13

Access and benefit sharing

Tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming

14

Integrating biodiversity values in decision-making processes

15

Businesses’ impact and dependencies

16

Informing on oversconsumption

17

Biotechnologies’ adverse impacts and risks

18

Harmful subsidies and incentives

19

Financial and non-financial resources mobilisation

20

Traditional knowledge

21

Participation of indigenous people and local communities, respecting rights, women, youth

22

Gender

- 1 And this even if the level of the 2030 target resulting from the negotiation should ultimately appear insufficient given the urgency to act to protect pollinators, for example.

- 2 Decision 14/8 of the Convention of the Parties to the CBD refers to other conservation measures as "a geographically defined area, other than a protected area, that is regulated and managed so as to achieve positive and sustainable long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including associated ecosystem functions and services and, where appropriate, cultural, spiritual, socio-economic and other locally relevant values".

- 3 Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy & Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability. (2020). Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap ; Waldron et al. (2020). Protecting 30% of the planet for nature: costs, benefits and economic implications; UNEP (2021). State of Finance for Nature, etc.

- 4 Although the Green Climate Fund also contributes to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, for example through Nature-Based Solutions.

- 5 Obura, David, and Sebastien Treyer (2022, forthcoming). " A “shared earth” approach to put biodiversity at the heart of the sustainable development in Africa". AFD Research Papers Series 2022-266.

- 6Songwe V, Stern N, Bhattacharya A (2022). Finance for climate action: Scaling up investment for climate and development. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- 7 “By 2020 at the latest, incentives, including subsidies harmful to biological diversity, are eliminated, phased out or reformed, in order to minimize or avoid adverse impacts, and positive incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity are developed and applied, in a manner consistent and harmonized with the provisions of the Convention and existing international obligations, taking into account national socio-economic conditions.”

- 8 The IPBES report indicates the key role of indigenous peoples and local communities within the territories they manage.

- 9 Widerberg, O. et al. (2021). Accountability of commitments by non-state actors in the CBD post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

- 10 Obura, David, and Sebastien Treyer (2022, forthcoming). " A “shared earth” approach to put biodiversity at the heart of the sustainable development in Africa". AFD Research Papers Series 2022-266.