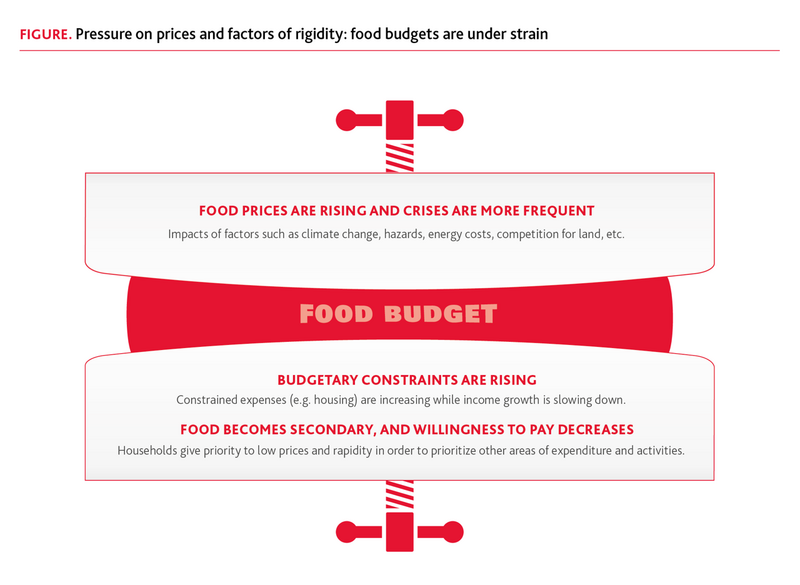

The COVID-19 crisis and then the war in Ukraine have caused a sharp rise in food prices in France,1 bringing the issue of access to food for all back to the forefront of public debate. Factors such as climate change, energy prices, health risks and protectionist trade policies could contribute to the continuation of these upward trends and to price shocks. IDDRI is today publishing a Study that highlights the high-risk situation created by this double-edged pressure–on the one hand, households under increasing constraints, and on the other, unstable and rising prices–and proposes, as a possible response to these tensions, a change in diets as a means of building resilience and flexibility for household budgets.

- 1

+20 % between 2022 and mid-2024: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4268033#tableau-figure2_radio1

The ‘secondary’ role of food in household budgets

Over the past several decades, the share of food in household budgets has fallen sharply: as income rises, the share devoted to food declines, while spending on housing, leisure and savings increases. This trend can also be explained by the stability of food consumption volumes and price increases in line with general inflation. In 2008, the share of the budget devoted to food reached an all-time low of 13.7% (INSEE, national accounts). In recent years, however, rising food prices and slower income growth have led to this share stabilizing or even increasing slightly.

At the same time, the proportion of pre-incurred expenditure1 (rent, transport, subscriptions) has risen sharply, reducing leeway for adjusting the food budget. From 12.6% of gross disposable income in 1959, it now accounts for more than 30% (INSEE, national accounts). Some increases, such as those in fuel prices, can even directly lead to a decrease in food expenditure through a budget adjustment effect in response to the constraint.

The trend is towards an increase in the weight of fixed expenditure in household budgets and a slowdown in purchasing power gains. As a result, pressure on food budgets is likely to increase.

The growing ‘outsourcing’ of food production

But the ‘secondary status’ of food is not just a phenomenon affecting households. It is accompanied by a shift in preferences for the allocation of budgetary and consumption resources. The last few decades have seen a steady increase in spending on processed products, pre-cooked meals and catering.3 The rise of digital and delivery services is further accentuating this trend, which reflects a gradual shift in food-related tasks from domestic production to commercial actors.

This outsourcing can be explained primarily by relative prices: processed products, driven by productivity gains in the agri-food sector, have become more competitive than raw products. It is also linked to social factors: the rise in female employment and the increasing value placed on free time have competed with the time devoted to food-related tasks, which households are now seeking to reduce. As a result, the time spent preparing meals fell by 25% between 1986 and 2010.4

Consequently, and with household budget constraints likely to increase, households do not have the necessary flexibility in their lifestyles to adapt without a significant loss of well-being. On the one hand, a massive return to home cooking seems unlikely, even if certain technological innovations could encourage it marginally. On the other hand, it would be risky to bet on households spending more of their income on food, even if their budgetary constraints were to ease.

Increased market segmentation and the risk of a ‘double-track’ food system

The food supply is structured around a variety of ranges (of products and prices) in order to satisfy diverse tastes, values and incomes. It is through this logic of differentiation that segments such as organic, plant-based and ethical consumption have mainly developed, which has led to these products being reserved for a small segment of the population with high incomes.

This segmentation can thus lead to a ‘double-track’ market: on the one hand, a standardized and accessible supply, but of lower nutritional and environmental quality; on the other, a high-end and valued supply, but reserved for a minority. This situation can therefore increase tensions around food by fuelling a sense of social downscaling for a growing proportion of the population claiming they are dissatisfied with their diet.

These increased constraints therefore come on top of an already unequal situation, which represents a significant breach of the ‘food pact’ between the state and society implemented after the Second World War, promising access for all to safe food that meets their preferences.

Future tensions on food prices

In parallel with the constraints mentioned above, the literature points to the risk of more unstable and rising food prices. Households would thus gradually find themselves caught in a vice, with no possibility of adjustment other than resorting to solutions that would degrade the perceived quality of their food and their freedom of choice (downgrading quality, skipping meals, food aid, etc.).

The surge in energy prices since 2021 has revealed the food system's dependence on energy costs. The increase in production, transport and processing costs has had a direct impact on food prices. In the future, the energy transition or geopolitical shocks could lead to sustained price volatility, with different effects depending on the sector.

Climate change is another major source of pressure on agricultural yields, both through shocks (e.g. weather events) and through changes in climate conditions (e.g. temperatures, droughts). These additional costs will have a lasting impact on food prices.

Finally, health hazards and food sovereignty policies aimed at protecting domestic producers or restricting trade are also likely to contribute to this increase.

Admittedly, productivity gains or economies of scale could partially offset these pressures, but the balance remains uncertain. Overall, food prices could experience both structural increases and greater volatility in the future.

Food choices under pressure: ways to respond

Public policy must take into account this growing tension between rising prices and tight budgets. But it cannot do so if it focuses solely on supply-side levers, which aim to ensure the lowest possible prices for French consumers through further liberalization or maximizing domestic price competitiveness. Indeed, such a strategy has at least three major limitations: (a) it would probably fail to generate sufficient price reductions to offset upward pressures; (b) it would offer no guarantee against shocks or increase the resilience of the food system; (c) it would have major social and political implications, particularly for the agricultural sector (e.g. decline in the number of farmers, enlargement of farms) and industry (e.g. incentive for concentration and reduction in the number of SMEs), or for consumption (e.g. increase in the share of imports).

Given these limitations, the priority is to improve the food environments in which households make their daily food choices, with a view to promoting a change in their practices. Indeed, a rise in prices does not necessarily imply a proportional increase in expenditure: reducing waste or substituting products can limit the impact, while allowing for flexibility in household preferences. With this in mind, shifting diets towards a reduction in the proportion of meat, alcohol and sugary products and an increase in plant-based products would ensure resilience in the face of price instability. If this shift in diets were to occur on a large scale–as it should–it would also have significant co-benefits in terms of health and the environment. However, due to the interplay between supply and demand, such a shift in diets would also have repercussions on the prices of animal products (downward) and plant products (upward). In this case, available studies conclude that, even if food expenditure increased slightly, it would remain compatible with medium-term income growth.5 In short, dietary changes can be seen as a factor of stability and resilience for household food budgets in an increasingly uncertain context, while also bringing health and environmental benefits.

The second issue is the risk of increasing inequality between households. Low-income households are now subject to greater constraints and specific obstacles in accessing healthy food that meets their preferences: pre-incurred expenses weighs more heavily (relatively) on their budget, with food already acting as an adjustment variable. This means that shocks to prices (e.g. inflation) or income (e.g. job loss) pose an even greater risk to these populations. They may also already feel dissatisfied with their inability to access high-quality, healthy or sustainable products. In this regard, improving food environments must go hand in hand with strengthening targeted social policies.

- 1

Kamyabi, N., & Fekrazad, A. (2023). The impact of gasoline price changes on food expenditures. Applied Economics Letters, 32(2), 174-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2023.2259591

- 3

As an example, spending on restaurants and canteens now accounts for 30% of total food expenditure, compared with 14% in 1960 (INSEE, national accounts).

- 4

Larochette, B., Sanchez-Gonzalez, J. (2015). Fifty years of food consumption: moderate growth, but profound changes.Insee Première. No. 1568.

- 5

See, in particular, Guyomard, H., Soler, L. G., Détang-Dessendre, C., & Réquillart, V. (2023). The European Green Deal improves the sustainability of food systems but has uneven economic impacts on consumers and farmers. Communications Earth & Environment, 4(1), 358; or the recent EAT-Lancet report, which reaches the same conclusion: Rockström, J. et al. (2025). The Lancet Commissions The EAT – Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems. The Lancet, 6736(25). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01201-2